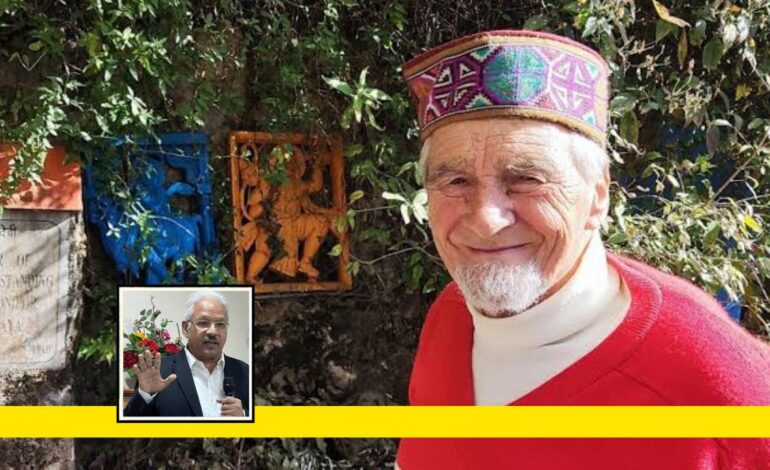

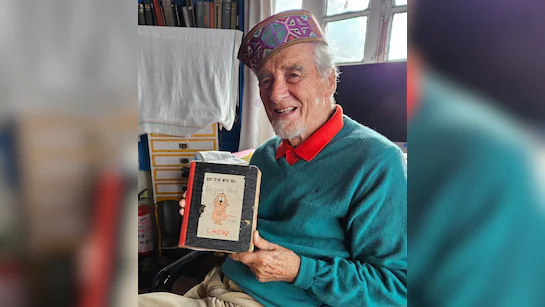

In the death of Bill Aitken (1934–2025) at the age of 91, India has lost not just a prolific travel writer, but a unique voice who saw the country not through the lens of a foreigner but as a seeker who chose to make India his spiritual and physical home. His long and eventful life, spent largely in the foothills of the Himalayas and the heart of the Deccan plateau, is a testament to the transformative power of travel, reflection, and deep cultural immersion.

Born in Scotland in 1934, Aitken came to India over six and a half decades ago as a hitchhiker. What was meant to be a youthful adventure became a lifelong journey of learning and writing. He settled in India, made it his home, and devoted his life to understanding its geography, people, religions, and contradictions.

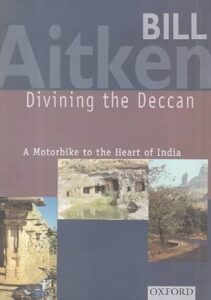

Though I have not read many of his works, the one book I did—Divining the Deccan: A Motorbike to the Heart of India—left a lasting impression. Published by Oxford University Press, it is much more than a travelogue.

It is a deeply researched, keenly observed meditation on a region that produced historical figures like Shivaji and Tipu Sultan and witnessed the birth and transformation of several faiths. The Deccan, through Aitken’s eyes, becomes a living, breathing presence—shaped by geography and reshaped by history. It was here that his “conversion” to everything Indian happened.

What struck me most, reading only the underlined portions of the book yesterday, was the depth of his insight and his quiet but firm rejection of popular narratives. He did not view the past through communal lenses. In fact, he was brave enough to question the glorification of certain figures and the vilification of others. His observations, such as Shivaji being portrayed in a Mughal-style cap and beard, while Tipu wore a Maratha-like turban, are not meant to provoke but to challenge our assumptions.

Aitken’s critique of Hindutva politics was equally sharp. After the demolition of the Babri Masjid, he stopped entering temples, choosing instead to linger in the courtyards to sense the spiritual energy from the movement of the devotees. He was drawn to Hindu philosophy, not its modern political avatars. That he chose to be cremated according to Hindu rites speaks volumes about the deep connection he felt with the spiritual traditions of India—though he had no patience for its bigotry.

His writing was often laced with dry humour and biting commentary. One such example is his take on India’s plumbing problems, which he links to the caste-based division of labour where the plumber, because of his social status, may never have used the equipment he installs. In another instance, he notes the irony of Dr. Ambedkar being forced to learn Persian instead of Sanskrit because the language of the gods was denied to a Mahar.

His passion for architecture and his understanding of political aesthetics shine in his lament about the Deccan. Despite Shivaji’s status as an emperor, the Marathas left behind few monuments, in contrast to the architectural marvels of even minor Sultanates. As Aitken points out, Muslim rulers not only had the technical skills to build with durability but also the artistic vision to locate these buildings for maximum visual and political impact.

Aitken had a remarkable ability to draw out meaning from landscapes. Nowhere is this clearer than in his interpretation of the Hindi blockbuster Sholay. For him, it was not just the actors or the storyline that made the film a classic, but the Deccan boulders southwest of Bangalore that gave the movie its haunting character. “The rocks of the Deccan are the real stars of the movie,” he wrote.

His love for the Sahyadri hills was deeply personal. He once remarked how their “soft-swelling roundness and crouching posture” reminded him of the Ochil Hills in Scotland, where he was born. His home in Mussoorie, which he named The Oakless, was a sanctuary, symbolic of his complete departure from his Western roots. Tragically, even before his funeral pyre had cooled, a group claiming to be from a Punjab-based Trust began to lay claim to his home—an ugly footnote to an otherwise beautiful life.

His relationship with Christianity was complex. He did not abandon his faith because of its teachings, but because he found its practitioners uninspiring. Yet, he retained the moral fibre and intellectual curiosity that many faith traditions value. Had he remained a Christian, I would have said that he must be turning in his grave to see the property he bequeathed to his loyal caretaker being fought over.

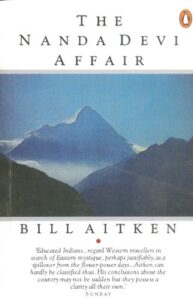

Bill Aitken authored over two dozen books—each one a mosaic of personal reflection, sharp observation, and historical knowledge. His books were part-autobiography, part-travelogue, part-social critique. He never claimed to be an expert, but his understanding was often more profound than those who wore the mantle of scholarship.

He had immense regard for Islamic education and once wrote about Mahmud Gawan’s madrasa in Bidar as an example of the intellectual vitality that once marked Muslim rule in the Deccan. While Hindu education remained restricted to a select few, he observed that institutions like the madrasa aimed to educate as many as possible.

What makes Aitken’s death so significant is that it marks the end of a generation of writers who saw India with honesty and affection—without agenda. He neither romanticised nor rejected India. He lived it. He experienced its beauty, contradictions, spiritual richness, and political complexities, and he gave all of it back to us in prose that was elegant, wise, and quietly radical.

He believed that longevity ran in his blood. And indeed, living into his nineties, he remained a seeker till the end. His books will continue to inspire generations of Indians and non-Indians alike. But what is perhaps more tragic than his passing is the loss of the home he built with love—a home that could have become a writer’s retreat or a museum of sorts, a place where the spirit of Aitken could have lingered in the rustling leaves and the view of the Doon Valley.

Bill Aitken is no more, but his words remain. May his soul rest in eternal peace.

Thank you Philip Sir . As usual your writing is crisp and insightful. Indeed,=right thinking Indians and people across the globe would continue to follow Aitken,’s perceptions .

Insightful Sir.

Good writing, Thank you Philip