The COP 28 summit ended in Dubai last month with much hype and moderate results while what the world needed was more of an emergency-response to combat climate change. As 2023 ends and a new year dawns, the gone year leaves behind odd and persistently grim signs in Kerala’s general climate.

In this tiny yet one of the most “biodiversity-rich” states of India, the new year begins with another dry spell. The days of December were hot; a decade ago the north east monsoon rains would have thrashed sky and earth alike at this time of year. “Let them take whatever they want. Don’t you worry, because they cannot take away our monsoon rains,” is the oft-quoted and culturally overrated remark of the King Zamorin of an old local kingdom of Kerala, about 500 years ago. He was talking about the colonists who came to the Indian coast from Portugal and England seeking pepper and other coveted Indian spices. As they plundered that natural wealth, the king found solace in a blind faith that the blessed weather of the region can never be stolen or taken away by anyone. How unfounded that belief was!

In Kerala, renowned for its moderate and pleasing climate, all the low and middle income people who can shore up their savings are buying air conditioners. As these hundreds and thousands of AC units work day and night to cool the house interiors, the load of heat that dissipates from them adds to the already rising “heat-island effect” in urban settings.

Forest fires and urban fires keep surfacing here and there. People seem to get more irritable and impatient while navigating their hot surroundings. What impact this rising heat will have on human relationships is a question that, in the immediate future, a psychology researcher might get interested in. Again, how will work and work output be impacted? Do we put our faith in technology to save us eventually? There are more questions than answers in the global apocalyptic reality of climate change.

In Kerala, whatever the season, the evenings used to be cool and windy. Now the trees stand at dusks without stirring a leaf as if they are in perpetual shock. Where have all the winds gone, one wonders. The roads start looking more and more deserted on summer days. Human mobility is impacted and the corresponding economic cost is not yet accounted for.

Flash Floods and Heat Waves

Only a couple of months ago, the planet witnessed flash floods from New York to China and India. Then, suddenly, the news was all about heat waves. June 2023 has been the hottest year globally in the last 175 years. 2023 July is probably going to be counted as the hottest month ever in the world’s history.

Simultaneous weather extremes are what we are witnessing; they manifest as floods combined with heat waves and a hot and humid atmosphere that suddenly turns into a cloudburst or torrential rain.

Sea ice is at record lows in the Antarctic. Naturally, all the ice that evaporated into the atmosphere has to come back to Earth somewhere. It need not be in the vicinity of the Atlantic Ocean. The trade winds, westerlies, and ocean currents push the water vapour around, often to the other side of the planet, and end up lashing out as cloud bursts and heavy downpours in the tropics and even in Europe. In 2023 March, the journal, Environment Research: Climate published a study that revealed that the extreme monsoon rainfall and accompanying flooding in Pakistan throughout the summer of 2022 was a direct impact of warming of the atmosphere in this country.

Often wildfires and urban fires will accompany the heatwaves. The ensuing loss to people’s livelihood, not to mention the loss of lives, is catastrophic. Sixteen cities in Italy reeled under the worst-ever heat waves a couple of months ago. Greece, France, Germany, Spain, and Poland also faced searing heat. Scientists have discovered that reduced carbon emissions can contain these extreme weather events but who will make the corporations and the governments work towards it?

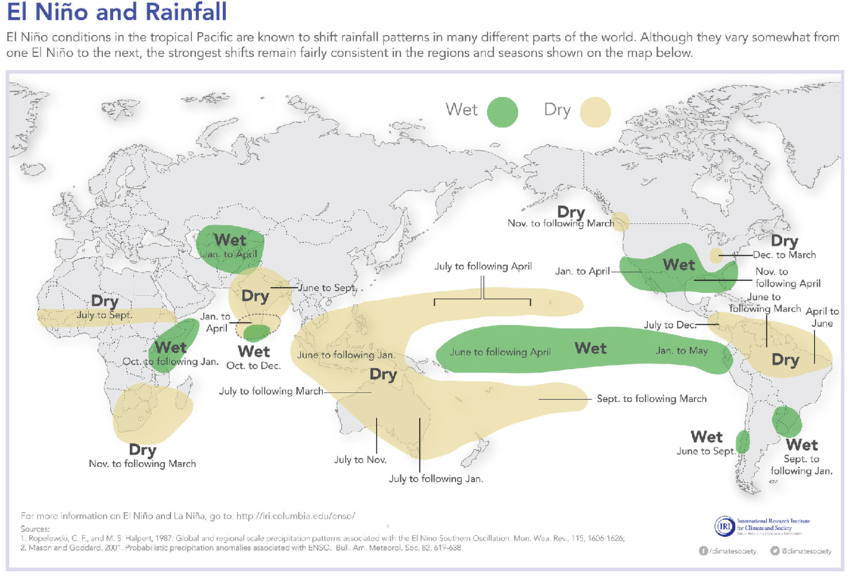

This was Officially an El Nino Year

El Nino, the abnormal and planet-wide heat fluctuation and oscillation that begins in the Pacific Ocean, had set in. The production of wheat, rice, and maize were hit. Some other scientific predictions say that sugar and soybean production will be pushed down to an all-time low. World is looking at an upcoming season of famine and food scarcity.

The UN weather agency has warned the world to prepare for extreme heat in 2024. ‘Science’ published a study in May 2023 quantifying the economic impact of El Nino and it reveals that during the 1982-83 El Nino, the global economic loss amounted to $4.1 trillion, and during the 1997-98 El Nino, the world suffered $5.7 trillion global income loss. Again, poor countries and poor people will bear the brunt of this loss.

Epidemic outbreaks often accompany extreme weather events. Scientists have expressed concern about a possible Malaria outbreak in Ethiopia due to the extreme heat.

The UN has appealed to the governments to take steps to protect lives and livelihoods from El Nino weather conditions. It is predicted that the worst effects of El Nino will manifest from December 2023 onwards and through 2024, and the planet most probably will cross the 1.5 degrees Celsius warming limit this year.

It is clear we are into the dog days of El Nino. Does India have a disaster management plan for this? In the past El Nino years, India had experienced below-normal rainfall. This year, most probably there will be a drought that will affect food security and farmers’ income. 2024 being an election year, let us hope the government at the centre has a plan to tackle the consequences of El Nino.

Monsoon in Kerala Used to be Different

In Kerala, exactly on the day when the schools reopen, after the summer vacations, on June 1st, the monsoon rains would arrive. The kids newly enrolled in class 1, would be seen literally swimming in knee-deep water in their raincoats, on their way to schools, as rain turns every road into a rivulet. The children would try to balance their walk in the wind by holding tight to their umbrellas, many with floral prints and lean steel skeletons that would bend backwards when the slightest gust of wind hits them. By some rare chance, there would be a shift of one or two days in the onset of the rains. Still, every year, the school season inevitably would open with thunder and torrent, resulting in drenched and dripping classrooms, wet bus floors, and soggy school bags.

In 2023, June passed without any rain in this part of the world. TV channels said it was El Nino one day, and the next day, they changed their narrative and claimed that hurricanes in the Indian Ocean and the Bay of Bengal were to blame. True, a hurricane did indeed sow devastation across western India. It caused so much that hundreds villages turned upside down. At the same time, in the northern part of India, more than 50 people died in the same week due to a heat wave. The period also witnessed simultaneous floods in the south Indian city of Chennai and in the country capital, New Delhi.

Traditionally, Monsoon in Kerala used to be precise in its entry, progression, and shape-shifting. The South Indian State had a rain calendar that will tell you the exact day when the rain changes its character- starting from June and ebbing out by mid-October. It was called ‘Kalavarsham’. A broad paraphrased translation reads quite philosophical. It would read as “rain of the essence of time”.

The calendar divides the season of rain into ‘njattuvelas’. The term, ‘njattuvela’ is a combination of two words, Njayar and Vela. Njayar, in Malayalam, means sun and vela is the word that denotes a time span. Thus, Njattuvelas represent the different time spans of the different positions of the sun. The monsoon rains change their character in each of the ‘njattuvelas.”

The monsoon rain that the local king, whom I mentioned at the beginning of this article doted on, is the rain of Thiruvathira Njattuvela. Thiruvathira is the star Betelgeuse, the red giant star, which is part of the Orion constellation. The rain-fed paddy cultivation in this region begins with the Aswathi njattuvela (njattuvela of the Sheratan and Mesarthim stars of the Aries constellation) and ends with the Swati njattuvela (njattuvela of the star, Arcturus). The njattuvela of Betelgeuse comes in between; and the rain of this njattuvela falls from the sky like thin, water ribbons, fluttering in the slow wind, but never stopping. The rain has the quality of a slow melody. This is the season to plant pepper seedlings and cuttings. The non-stop rain helps these plants take root.

The above memories of rain are from a decade ago. Of late, the monsoon rains have been highly erratic. The corporates and colonists have eventually taken away the rain from us, Keralaites including this writer. Climate change and global warming are immediate realities for us. Sometimes, unexpectedly, the otherwise famished monsoon shapeshifts into a sudden, dramatic, and cruel downpour like the one that happened in 2018, inundating our entire region and taking away many lives and livelihoods.

Cloudbursts and landslides came along with and added to the devastation. Then we faced long spells of drought and heat. Farmers do not know when to sow or how to keep their crops alive through the summers that last perpetually. When the rain comes, the fields flood in no time, and again, the crop is lost.

This December, the paddy farmers were the worst hit. Muhammed Kutty, a long-time successful paddy farmer from Malappuram district in Kerala, has his 10 acres of paddy- cultivated on leased land- incessantly attacked and almost destroyed by an unprecedented virus infestation.

He said that the agricultural experts from whom he sought help indicated that the lack of good sunlight (the skies used to turn lovely blue in December-January) and high humidity owing to overcast sky instead of the usual dry winds, are the reasons.

The vegetable farmers were taken by surprise when the usual monsoon rains in June were delayed in 2023. Those who planted Chinese Potato, for which the June-July rains trigger the primary growth onset, were struck by the delay in monsoon. They had to spend huge sums to hire motors and pump water from nearby and faraway sources towards irrigating the crop.

The farmers are now generally aware that climate change is a reality and that they have to be prepared for unexpected droughts and rains playing havoc. Paddy farmer Jaisal says that year after year, they are finding it far more difficult to protect the crops.

Thus the year 2023 ended with an apprehension that worst is yet to come. The connection between climate change and monsoon rain is already an established fact. This interconnectedness is paramount because the monsoon affects a fifth of the total population of the world. A 2021 study published in the journal, Earth System Dynamics, collated reliable data to show that climate change is causing a significant increase in monsoon rainfall. This is a finding which warns us that our region, Kerala, is going to be dangerously flood prone. When it rains, it pours but there is also a parallel phenomenon of the weakening of monsoon winds over the warming oceans at times, which will result in droughts too. Climate change overall makes the summer rains sparse but causes heavy flash downpours and flooding too in summer.

The idyllic countryside with its soothing climate and the monsoon tourism that was mushrooming and thriving seem to be lost dreams from the past. The monsoon has been the blood that flows in our veins and through the arteries of this land; when that dries up, we will be a changed people with no anchor, no refuge.

References:

Katzenberger, A., Schewe, J., Pongratz, J., and Levermann, A.: Robust increase of Indian monsoon rainfall and its variability under future warming in CMIP6 models, Earth Syst. Dynam. 12, 367–386, 2021.

To receive updates on detailed analysis and in-depth interviews from The AIDEM, join our WhatsApp group. Click Here. To subscribe to us on YouTube, Click Here.

God’s own country needs to sit up and take notice of the stark facts that have been highlighted in this article . The authorities of the state cannot be smug claiming that they are number 1 in social indices . There are bigger battles to be fought . Ignoring it will be at the cost of all that Kerala has gained over many decades from the pre- independence period

Kerala is a state of ironies. Flying over it, you see so many rivers and rivulets. Yet there is a stark lack of 24 hours potable water available to the common man. And that is just one example.

The lack of the political will to improve the state by successive governments is the main reason for this state of affairs. And no, the BJP is not the answer.