Coherence and Style: On Abul Kalam Azad’s Towers of Silence

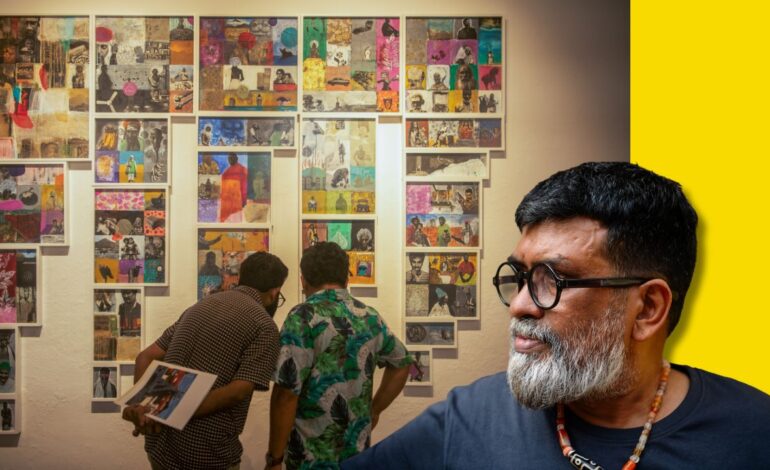

What happens when silence doesn’t whisper but stares back—painted, posed, and provocatively still? Towers of Silence might sound like a meditative retreat, but Abul Kalam Azad’s latest solo show is anything but hushed. Set inside a bustling Fort Kochi café, this isn’t your average art display, it’s a conceptual ambush disguised as a photography exhibition. Azad doesn’t capture reality; he contorts it, coats it, questions it. His photographs don’t speak—they withhold. And in that withholding, they dare us to see beyond the frame. Welcome to the strange theatre of dissemblance, where every pose is a provocation and every silence, a trapdoor.

Abul Kalam Azad (b. 1964) is a trailblazer of avant-garde photography in India. Defying traditional confines, Azad ranks among India’s early pioneers who ventured into conceptual photographic experimentation. Fearlessly challenging established norms, he offers a novel perspective, expansively redefining photography’s artistic possibilities. A daring and inventive printmaker, Azad has cultivated a distinctive approach, deliberately etching, doodling, and sewing onto negatives and photographic prints, thereby subverting the conventional reverence for print surfaces. His primarily autobiographical creations aim to dismantle the colonial gaze, unearthing memories from beyond the colonial and partition eras while scrutinizing accepted photographic conventions. They attempt a re-reading of contemporary Indian history – the history in which ordinary people are absent and are mainly represented through beautiful images and icons.

Azad has been the recipient of the Charles Wallace Award and other prestigious grants, and has worked and exhibited internationally. His current projects focus on a search inside South Indian maritime history and connected cultures, inspired by ancient literature, folklore, and rituals. He is currently based in Wayanad, Kerala.

Azad’s solo exhibition titled ‘Towers of Silence’ opened at Kashi Art Galleries, Burger Street, Fort Kochi, on 8 February 2025 and will remain on show till 30 April 2025.

Towers of Silence is an odd name for an exhibition housed in one of Fort Kochi’s busiest cafes. One expects an atmosphere of contemplation, of reverential silence. Yet the space is anything but. The clinking of cups, the hum of conversations, the constant movement of people in and out—all of this runs counter to the meditativeness that the title seems to evoke. To be fair, this is a gallery with a cafe: we first walk into a dedicated gallery space, and then into the table space. The busy nature of the space, compared to run-of-the-mill white cubes, is undeniable.

In his first solo show in five years, Abul Kalam Azad is displaying a variety of works from his recent output. There is the eponymous series that is displayed as a semi-installation, with the framed prints forming a design that looks like pixelated icicles. These are photographs that have been painted over, and one can see turquoise and lilac among the pastel-like palette it deploys. A handful of painted photographs from his series Men of Pukar are also displayed. There is the series Sema, which reimagines mythical and historical figures whose shadow continues to fall upon Indian society—these are prints on wood. Two large prints, one featuring a dog and the other featuring pigs, from the series Totems and Taboos find their place. Deep inside the cafe, on the farthest walls, Cinema Blues is almost hidden from view. This is a series based on objects collected from cinema halls, combined with cinema posters, and later reimagined through digital technology.

The range of media is rather expansive for a photography exhibition. The techniques on display include hand-painting, digital prints, serigraphy and photolithography. What is on display looks like a platter of Azad’s personal menu of photographic recipes, as opposed to usual photography exhibitions, which are focused around a theme, series or, more rarely, a single medium.

In spite of the physical and logistical constraints, the show has a pleasant coherence. It is, first and foremost, a display of style more than anything. This is easy enough for a painter, sculptor or multimedia artist to achieve, simply because there is a tradition of accepting stylistic unity as the sole basis for an exhibition in these disciplines — not so for a photographer. But the question can dwelt upon further in the context of this exhibit.

What makes an artist’s style coherent? This question lingers over any spectator of Towers of Silence, especially given the varied subject matter—a car, different kinds of men, a woman, leaves, an iron box, seemingly random textures and so on make up the surface of these images. There is no singular visual theme or political throughline to anchor the series or the exhibition as a whole. Such normal expectations do not take us far.

Instead, we ought to start our inquiry into style with the most obvious feature of the images—that they are all manipulated photographs. What is the artist doing when he manipulates photography? Photographs are valued for a single quality: their verisimilitude. If a photograph does not resemble, it isn’t of much use. One could think of abstract photography as an exception to this. But it is equally true that abstract photography gets its richness from its straddling of the line between verisimilitude and a formalist gaze.

Azad’s work, on the other hand, is a deliberate subversion of photographic verisimilitude. How can we name this tendency? What, really, is the opposite of verisimilitude? The common answer is illusion, but an illusion is actually another word for verisimilitude—something that mimics reality. An ordinary photograph is an illusion, a chemical or electronic mirage that is suggestive of a referent that is supposed to exist. The opposite of verisimilitude, as far as I know, has no name. It would signify the quality of appearing to be truthless while, in fact, being truthful; a fictitious path towards truth. This quality is visible in post-realist art, which took great pain to avoid any sign of realism.

One may easily call this anti-verisimilitude. If this coinage seems too explicitly negative, we may consider calling it dissemblance—a word that suggests a bit more than mere falsification, but a deliberate play with perception, a way of withholding elements. This term was first used by American writer Darlene Clark Hine, in an entirely different context and with a different meaning. We may recast the term for our purposes. Dissemblance, for us, does not deceive; it just takes apart in an unsettling way. Dissemblance is not mere dismantling. It is the conscious reorganisation of resemblances.

Azad’s images exemplify this gesture of dissemblance. While they do not dissolve into reality, they also do not fully reject it. Instead, they inhabit a space of withheld legibility, forcing the viewer out of ascribed habits of viewing photographs. If photography is by itself a means of throwing a spotlight onto a moment and a scene, these dissembled images are a means of doubly spotlighting an element of a scene. These elements are the actual lubricants that produce coherence in Azad’s work. They are anthropomorphic in some sense, as is all of photography. Every amateur photographer knows that any subject, human or non-human, has a “face” and a “look”. Azad shows that they also have a pose.

Azad’s dissemblage photography is dedicated to exploring pose and posture. His figures, be they humans, animals, machines, tools or products of nature, are like mannequins caught in the process of articulation, occupying a realm where they are both estranged from their own bodies and yet defined by the precise way they hold themselves. The photograph, in this mode, is neither a window into the world nor a pure fabrication—it is a fictional architecture of truth, where postures are composed to convince us that there is a deeper force at play.

Every subject in this exhibition seems to pose, whether human, object, or landscape. There is a peculiar stiffness to these images—bodies contorted into staged, unnatural angles, as if caught in a moment of artificial stillness. Even inanimate objects take on an eerie formalism, as if self-conscious of their own positioning within the frame. His figures resemble stringed puppets, toy objects, and stiff dolls, held in a moment of poised suspension. It is as though the camera has not just captured them, but posed them with an awareness of their own display.

If the figures in Azad’s photographs resemble puppets, then they inevitably suggest the presence of a puppeteer. But who, or what, is pulling the strings? This is the pivot on which his social commentary hinges—by staging his subjects in postures that appear contrived, self-conscious, or unnaturally composed, Azad draws attention to the unseen forces that shape human presence and self-presentation. His photographs are not merely about the figures within them, but about the historical, cultural, and ideological apparatuses that dictate how bodies exist in the world, how they perform, and how they are made to perform.

This is where Azad’s method departs from both social documentary and traditional portraiture. A documentary image seeks to reveal an external reality, while portraiture aims to distill an essence of individuality. But Azad’s figures—human, object, or landscape—resist such containment. Their stiff, suspended quality suggests that they do not fully control their own articulation. The unnaturalness of their pose is not a failure of realism; it is a gesture toward the invisible histories that dictate how one should stand, sit, or even exist. It is as if Azad is asking: What scripts do we unknowingly follow? What traditions choreograph the movements of our bodies and our minds?

The answer is neither obvious nor singular. If there is a puppeteer in these images, it is not an individual but a complex of historical conditions, ideological structures, and unconscious inheritances. Azad’s photographs make these forces visible not by pointing at them directly, but by showing their effects—by turning subjects into posed figures, whose strained postures suggest the weight of forces just beyond the frame.

Pablo Picasso is supposed to have said, “When art critics get together, they talk about Form and Structure and Meaning. When artists get together, they talk about where you can buy cheap turpentine”. The days in which artists were so humble are long gone, but photographers are still expected or assumed to be so. They are reduced to being observers rather than creators, witnesses rather than architects of meaning. The difficult thing about writing something about Azad is that he is not a humble photographer. It is not that we do not have ambitious photographers at all. Ambition in photography is associated more with logistical grandness: the scale of the project, the access to subjects, the execution of a challenging shoot.

Azad’s ambition is not logistical but conceptual—his photography does not seek grandeur through spectacle, but through a withdrawal from the obvious, a refusal to let the image function as mere representation. This is best understood as an act of anachoresis—a word derived from ancient Greek, meaning a retreat, a stepping back from the dominant order. In religious traditions, anachoresis refers to the withdrawal of ascetics from the world, not to escape it, but to see it more clearly. Azad’s work performs a similar movement. His images retreat from photography’s claim to truth, from its documentary impulse, from its conventional hierarchies of vision. In doing so, they reveal something more profound—not the world as it appears, but the unseen arrangements that shape how it is perceived.

This retreat is not into silence but into a different way of speaking. His subjects, poised and rigid, resist easy readability; his layered surfaces obscure as much as they reveal. And so, the title Towers of Silence takes on a new resonance. It does not signify stillness or a high ground of contemplation in the usual sense. Rather, it is a silence that holds something in reserve, a retreat that is not a disappearance but a reconstitution of meaning in its own time, on its own terms. If Azad’s photography withdraws from verisimilitude, it does so not to abandon truth, but to find another path toward it—through dissemblance, through pose, through an art that speaks most clearly in its refusal to explain itself.

Photographs by Biju Ibrahim

Awesome https://tinylink.info/10Myk