Oppenheimer- The Said and Unsaid

Oppenheimer is a biographical film on the most controversial physicist of the 20th century by the celebrated Hollywood director Christopher Nolan, maker of Dunkirk (2017), Interstellar (2014), Batman Vs Superman Ultimate Edition (2016), Inception (2016) and a host of other films on eclectic subjects. He is a megastar amongst Hollywood’s film directors.

Robert Oppenheimer, was an American Jew, whose intellect, perhaps matched that of Albert Einstein, the German-Jew who, fleeing Hitler’s anti-sematic Nazi Germany in 1932, found a home in the United States of America and was celebrated there. Einstein’s genius for physics was matched by his ethical conscience. The same cannot be said of J. Robert Oppenheimer, who came to be known as the ‘Father of the Atom’ bomb and the man who headed the Manhattan Project, comprising a team of scientists working on the Atom Bomb in utmost secrecy and with great speed to have it ready before Hitler’s Germany did during World War II (1939-1945).

The ultimate tragedy was that Oppenheimer (the subject of the film) was unable to fully comprehend the destructive potential of the bomb until it was too late.

Nolan’s film goes easy on these ethical considerations though there is a sentimental approach adopted by the director in the last shot of the film, when, in response to Einstein’s fear that the Atom Bomb may destroy the world, Oppenheimer, in gigantic close up (the film is shot in IMAX, a huge screen format designed expressly to overwhelm the viewer), he says “we already have,” meaning have destroyed the world. This lone statement does not compensate for the rest of the film which evades the ethical implications of creating a monster that can destroy the world in a trice.

The film’s structure is staccato. It begins with Oppenheimer’s trial instigated by the notorious anti-Communist Senator Joseph McCarthy, who was convinced that Oppenheimer was a traitor, because of his communist sympathies, at a time when very many intellectuals, became either members of the Communist Party of America or fellow travelers, having witnessed the failure of American capitalism when the share market collapsing in 1929 and leaving the economy of the nation tottering for a decade and millions struggling for their daily bread. The principal villain in the trial in the film, is Lewis Strauss, a mediocre scientist who thinks he has been wronged by Oppenheimer. Strauss (played powerfully by Robert Downey Jr.) is the driving force of the story and scenes from Oppenheimer’s life are intercut with Strauss’s ‘testament’ at the trial.

Cillian Murphy’s portrayal of Oppenheimer is involved, in an old fashioned style of Method acting. He lives the part, in accordance with his conception of what the man he is playing may have been like. It is through his portrayal that Nolan’s film acquires both its thrust, and aesthetic ambivalence.

It is important to place the real Oppenheimer alongside his onscreen version. The film’s Oppenheimer, for all his brilliance, comes across as a vulnerable, and, on occasion, an indecisive man. In other words the victim of his circumstances. It is an interpretation that suits the American audience, still floundering between Christ and Freud, and also, unable to give up its appetite for the overweening comforts of the material world and its attendant perversions.

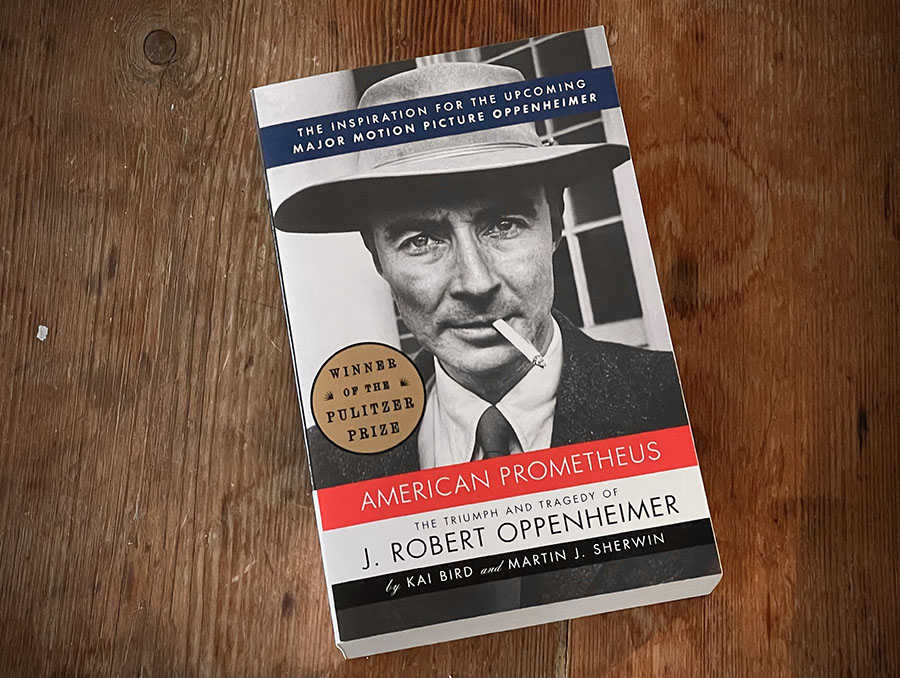

Nolan, who is also the scriptwriter of the film, sees Oppenheimer as a man obsessed with his work and yet politically aware, who is grateful in an understated way to the American State for providing him the opportunity as it turns out, in retrospect, of playing both Faust and Mephistopheles at the same time. The script is based on J. Robert Oppenheimer’s biography, American Prometheus by Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin, a book that won a Pulitzer Prize.

It is difficult, even today, for the U.S. and its citizens (a vast majority of them) to accept the fact that the Atom Bomb created by Oppenheimer and his team in the Manhattan project had paved the way for the destruction of the world; an observation proven by the proliferation of nuclear weapons all over the world today, with the U.S.A leading the way, followed by Russia (the erstwhile Soviet Union) and China, in that order. All it needs is a lunatic, driven by extreme insecurity to push the Button, to provoke an instantaneous reaction from others to do the same, for the entire world to go up in flames in seconds.

In the film what is stated clearly is the need for America to make the bomb before Nazi Germany does and uses it on the Allies. The outcome of the Second World War is seen to be hanging in the balance. Nazi Germany loses the War and surrenders, but its ally Japan, on its last legs, with hardly any resources–military and financial left, fights on gamely, and possibly may hold out for another month.

The Atom Bomb is dropped over the islands of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, nevertheless. Three hundred thousand people die in moments and very many others are maimed and crippled for life and are afflicted by radiation poisoning in varying degrees. Both Hiroshima and Nagasaki are completely destroyed. The real reason for dropping the two bombs was to judge how destructive they could be. As later facts were to prove that the United States of America, immediately after the end of the war in 1945, fearing the rise of communism and Soviet Union’s ever increasing political power, had actually planned to use the A-Bomb over 66 cities of the Soviet Union if the situation got ‘out of hand’. Surely Nolan, Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin were aware of these facts. The film is silent about this crucial detail and the U.S. Government’s deliberate, completely inhuman dropping of the bombs over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and to use the Japanese as Guinea Pigs, giving an absolute racist angle to the exercise. In addition, there are no images of the aftermath of the bombing and the complete destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the film.

The mounting of the production, in layman’s language, is gorgeous. Nolan, is perhaps, the greatest showman of our time. He has an exceptionally talented team working to help realise his vision. Hoyte Van Hoytema (Cinematography), Jennifer Lame (Editing), Jake Cavallo (Art Direction), Ruth De Jong (Production Design), Clair Kaufman (Set Decoration), Oliva Peebles (Set Decorator – New Mexico Unit), Scott R. Fisher, Laurie Pellard, Mario Vanillo, Vincent Vanillo (Special Effects Team), Ellen Mirojmick (Costume Design) and a host of others who worked together to give the film its completely authentic look. The Los Alamos township and testing sight is a most impressive combination of engineering construction and art direction.

The scene of the testing of the Atom Bomb is certainly awe-inspiring but what follows later in the story in the Los Alamos township auditorium when Oppenheimer informs his co-workers, not all of whom are scientists, but have been a part of the project, about the devastation caused by the two bombs dropped over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, is both scary and nauseating. Every member of the audience in the auditorium is cheering manically like a football hooligan! The film does not clearly say anything about the complete devastation of the two cities but is jubilant about the total military defeat of Japan.

There is an attempt throughout the film to deflect attention from the real issue, that of the destruction of human civilisation till 1945, and, not just the poisoning of the human consciousness but a fatalistic acceptance of the new status quo, that is, nuclear weapons shall remain in permanent existence, and the world, henceforth, shall live in fear all the time.

Nolan treats his story differently. He treats President Truman as a callous buffoon in the scene of his meeting with Oppenheimer, who tries feebly to tell him of the enormous destruction caused by the two A-bombs. Truman responds with, “But we brought our boys home (meaning the Army) safely.” When Oppenheimer, with tears in his eyes, mumbles something about the destruction caused, Truman, draws out his handkerchief and offers it to him and tells his friend, “Take this cry baby away.”

American cinema, certainly in the last fifty years has been gravitating towards a language of misleading heroism and hence machismo. The trial of Oppenheimer, which is the pivot of the film, is cut up in many bits. In a portion, the physicist is called before a Committee of Jurists, mostly from the Armed Forces, who question him about his attitude towards the Atom Bomb (he doesn’t want any more to be made, though he is aware that it is going to be a futile exercise) and, of course, his integrity and character. Strangely enough, Leslie Groves (finely played by Matt Damon), a senior Army Officer, Supervising the Los Alamos operations during World War II, comes to his defence.

Oppenheimer, the former Communist sympathiser, makes his compromises with the System steadily and is given official recognition, not unsurprisingly. Nolan makes a film, with no nuances, saying all the right things, which is visually and aurally breath-taking, but far away from what we consider to be a universal truth.

Excellent analysis