When I heard of K.K Kochu’s demise, there was a palpable sense of loss which rose within me; this was not because I had known him personally, neither have I been under his caring mentorship like many other dalit-bahujan-adivasi activists and intellectuals; it was a sense of loss that was primeval, a deep sense of displacement like one had lost an ancestor. I had known him mostly through his books which I lapped up as a young researcher in JNU struggling to understand the intersections of caste, patriarchy and social formation in South India. K.K Kochu, or Kochettan as he was endearingly referred to by some of his friends and associates, was not only an organic intellectual in the Gramscian sense of the term, he was also a frontrunner in formulating a scholarly premise for dalit critical theory and scholarship in Kerala.

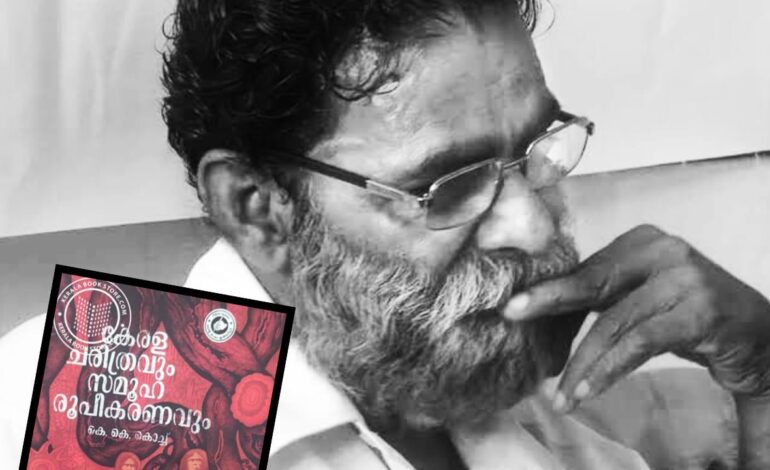

His ‘Kerala Charithravum Samooharupeekaranavum’ (Kerala History and Formation of Society) still stands out as a work which challenges the very basis of conventional historiography in Kerala. What was truly brilliant about the work was the shifting of the locus classicus to the subaltern classes and castes, social groups whom he referred to as pulp communities. This was a rupture from the conventional historiographical practices of using predominantly sanskritic works as primary sources which would lead to the region’s past revolving around socially dominant groups.

While we can debate about the work, it is a must-read for every history scholar as it opens up a new vista of alternate history; one which emerged from the grassroots, weaving together scattered narratives to a coherent whole rather than following the top-down path of grand narratives.

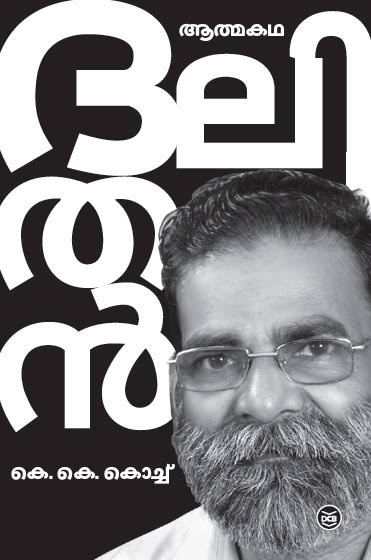

‘Because I was tagged as a Naxalite, initially the village folk did not befriend me. Slowly the distance between me and people started diminishing. What helped the situation was my identity as a writer and not my politics. People who were interested in politics and literature were the ones who started paying attention to the various topics that I was discussing.Most of the evening gathering became discussion forums. Soon O.V Vijayan, M. Mukundan, Kakkanadan, P.Valsala started entering the conversation which would usually revolve around long form stories from Malayala Manorama and Mangalam weeklies or novels from Muttathu Varki. In the discussions regarding cinema, it was not only Aravindan and Adoor Gopalakrishnan that found space, but classic cinema from around the world. Meanwhile, it was mostly those from the lowest strata of society that showed a lot of affection towards me. Predominantly, they were Adivasis, especially Paniyas. Those who sold arrack illegally, sex-workers, barbers, Visvakarmajas, domestic workers who were employed by middle class migrants who had moved to Wayanad and suchlike became part of my circle of friends. People started approaching me for writing download 708their requests and petitions to the Village Office and Taluk Office. It became my responsibility to get bail for those who were arrested by the excise officers for selling ‘raak’ (a kind of alcohol).In this manner, I could develop and sustain an organic relationship with people beyond politics; though I was constantly anxious about the situation at home.As both chachan (father) and Amma would go for daily wage manual labor, their daily sustenance was not an issue, but we did not have clothes, household utensils or domestic appliances. Once I reached Kalpetta, the first thing that I bought with the money that I had received as payment for the play which was published in the Vishu supplement of Mathrubhumi weekly was to buy utensils…

– K.K Kochu, in his autobiography, Dalithan

The excerpt from K K Kochu’s autobiography, which is very aptly titled as ‘Dalithan’ is quite telling of the many lives he lived – as a human rights activist, writer, intellectual and as a dalit. It is also an oft repeated trope that one sees among early dalit activists and intellectuals who while making social interventions and helping others would be constantly mired in their own personal trajectories of hardships. Another mark of stark difference between dalit intellectuals and other leaders was that one would not find the logic of ‘using people as tools of revolution of emancipation’ among the former. They identified as part of the most marginalized and were one with them; so rather than thinking of people as mere instruments in a larger whole, early dalit activism was marked by people-centered bonds beyond ideology.

Another significant mark of difference between K.K Kochu’s writing and the works of other early dalit writers was that Kochu would never let dalit history be reduced into a history of only victimisation, it was rather important for him to talk about a dalit knowledge and a dalit intellectual sphere and dalit aesthetics and so on. He would constantly portray his own life experiences and the life-histories of other dalits as a cross section of society and interrogate systemic issues than reducing them to travails and ordeals of individuals.

Gopal Guru, renowned scholar and political scientist has made a compelling argument regarding the skewed mode of theory production in the Indian academia – where dalit scholars are expected to provide narratives based on their experiences while those belonging to elite background would build theory based on these narratives. It was a sort of presentation, where theory was considered to be the domain of the savarna.

K K Kochu’s writing dismantled this practice of academic gate-keeping. He produced theories and counter-arguments while weaving experientiality into those exercises of knowledge production. He did not refrain from integrating black American, African and Indian philosophies into his own writing which has not only created a solid base for dalit and sub-altern intellectual discourse but has also shaped the way in which anti-caste discourses are framed in Kerala today.

K.K Baburaj credits K.K Kochu with having recast Mahatma Ayyankali, as the leader of Kerala Renaissance at a time when Mahatma Ayyankali was still being referred to as ‘Pulaya Raja’ and ‘leader of Pulayas’ by other scholars. The same conviction can be seen in K.K Kochu’s writings about Poykayil Appachan and Sree Narayana Guru where a strong case for not framing them merely as caste-leaders was made by Kochu who portrayed them as shapers of Kerala’s progressive character.

Much before the term intersectionality was coined, K.K Kochu, through his writings, would attempt to integrate the struggles of women, adivasis and dalits on a theoretical level. He believed that dalit activists should take a keen interest in the struggles of other oppressed and minoritized communities. In his writings one could see how he identified with the radical Left struggles and activities in the early days of activism and how soon he developed notes of dissonance with the movement and found himself attracted to Ambedkarite thought. However, he also found convergences in Leftist and Ambedkarite philosophies.

A strong element of dissent with the system could be seen as a preponderant aspect of his life and writings even while being in a government job (in fact, he held several positions in different government sectors in his life); this was another exceptional feature of K.K Kochu’s life, but it also informs us about the interplay of individual liberties and the state (or its excesses), even in the tumultuous emergency and post emergency period. If one goes through Dalithan with a close comb, it reads as a cultural history of the politics of modern and contemporary Kerala.

Black feminist author Bell Hooks has opined that it is often not the gaze from the centre, but the view from the margins which offers a more appropriate vantage point on the functioning of power on varied sections of the population. K.K Kochu offered that much required view from the margins, one which displaced the state-centric views of authority and looked at the oppressed as the focus of attention.

Unfortunately, his thoughts and writings were far ahead of his times and his contemporary society was quite unkind to his genius. Him being vocal about his vulnerabilities and absolutely transparent about his political positions which contradicted mainstream views on many a subject also put him at a difficult position. Which meant he did not gain the larger social acceptance that he should have received decades ago. But like a lot of philosophers who are not honored during their times, K.K Kochu would be credited with paving the way for the emergence of a strong awakening in Kerala society in recent times, especially to issues of caste oppression and system injustice.