The Infinite Violence of Everyday: Taking Elimination of Violence on Women Seriously

On November 25, 2024 as women across the globe took out marches to raise awareness against the violence faced by women, I sat on a panel organised by the NSS wing of my University to commemorate the International Day for Elimination of Violence against Women, listening keenly to Atheetha, a young doctoral scholar at Mahatma Gandhi University (MGU). She talked about emotional violence- the intangibleness of which makes it a difficult category of violence to speak about with evidentiary proof, which law frequently asks of women, yet the concrete force of which wrecks women’s lives.

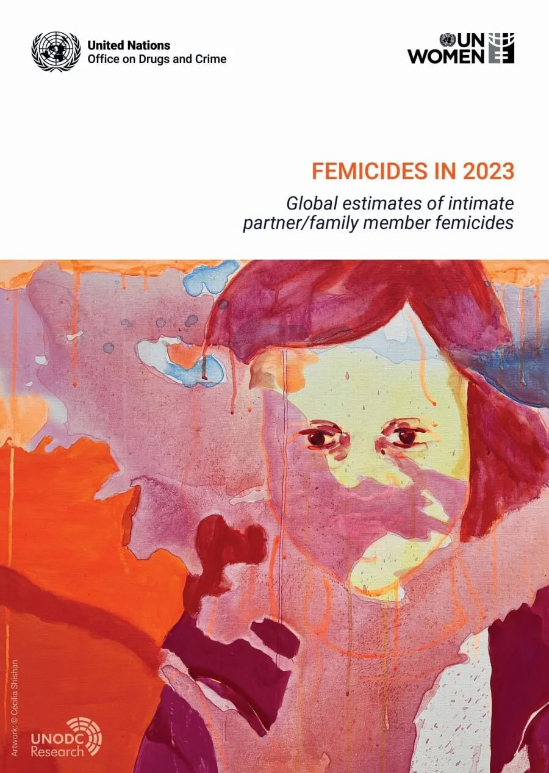

The panelists including me had decided to look at the structural reasons for violence against women, but also engage in looking at everyday violence- its pervasiveness cloaked in the invisibility accorded by its ordinariness. Disturbingly, even the concept of everyday violence includes death for women. The statistics will alarm the most complacent of us who feel we have made strides in women’s safety and autonomy. The report released by UN Women and UNODC, Femicides in 2023: Global Estimates of Intimate Partner/Family Member [Read Here] revealed that femicide—the most extreme form of violence against women and girls—remains pervasive with 85,000 women and girls killed intentionally in 2023 alone. That is one woman is killed every 10 minutes. Sixty per cent of these women died at the hands of their intimate partner or family member making home ‘the deadliest place for women’.

Closer home in Kerala, the next day had dawned with the news of a 26-year-old woman who was hospitalised with injuries from physical domestic violence. She had only recently returned to her abusive husband after retracting complaints of domestic abuse filed earlier against him. In Kerala as in India, the concept of honour is linked irrevocably to the heteronormative caste-pure family; the home is a demonic space for domesticating women into submission at the altar of honour and respectability. Abuse within the home involving women is to be tolerated, autonomy is to be set aside in matters of love and desire and even the State’s mechanisms choose to conciliate the woman to return to her home, seen multiple times including in the Hadiya Case.

Dowry-related harassment is still widespread in Kerala which prides itself on being an exceptional place of development and political progressiveness. The family is also central to the choices of labour made by women discouraging women from either entering the workspace or restricting their choices of labour. Kumkum Sangari has written how unpaid household labour is given the framework of lasting personal relationships which are not and cannot be measured in terms of time and money.

A NITI Aayog report mentions that women in India spend 9.8 times more time than men on unpaid domestic chores, against a global average of 2.6 per cent. Feminist scholars like Neetha N have used the concept of gendered familialism to explain the limited choice of women in labour, the assumption that the welfare of family members is best assured through women’s unpaid work at home. In her work on Domestic Work, she shows how this pattern is contradicted when class and caste are taken into consideration; the domestic as workplace is also beset with violence.

Dalit women are mostly employed in cleaning with more respectable cooking positions reserved for upper-caste domestic workers. Recently it was reported how rampant badli/proxy work is in government sanitation jobs where dominant caste women were employed under the quota system but the actual work was done by Dalit Valmiki women deprived of government-mandated pay and medical insurance benefits.

Caste practices and conduits still enable upper-caste households to get underage girls from ‘back home’ as domestic help while violence is ingrained in new forms of recruitment of migrant women to work in cities. Neha Wadhwani’s study on the outmigration of women from Jharkhand as domestic workers begins with a poignant description of domestic work as the only way out from their households, the other being joining the Maoist movement.

Violence following women into their workspaces was brought out in its brutality in the recently published Hema Committee report on issues faced by women in cinema. One particular act of violence that was brought out in the subsequent discussions on the report was the circulation of atrocity images of sexual assault, innocuously termed as the ‘souvenirs’.

Akin to ‘trophy images’ of sexual violence and murder’ captured by perpetrators of violence during conflicts and war, these images of sexual harassment at the workplace imprint on us how women’s lives are lived anticipating and experiencing violence daily. Digital spaces have emerged as yet another place where women are victims of cyber-violence where the consequences of being victims are increased surveillance, curtailing of mobility and slut shaming, and restrictions on the use of digital spaces for women.

Even a workspace like a university is beset with violence where women in their individual capacity as well as part of the independent women’s forums battle everyday sexism, and infantilisation of their intellect and capabilities, to put forward the politics of freedom from patriarchy. A woman doctor was killed in Kerala during duty, at the same time hospitals and medical practitioners are spaces and persons from whom women face morality policing as well as experience a complete lack of autonomy over their bodies. We have failed to learn from the sex workers movement that gave feminists new ways of looking at labouring bodies and we have fallen short in our solidarity with queer persons and women of disability.

The instances of spectacular violence and exceptional violence like the 2012 Delhi gang rape and murder, and the gruesome murder of the trainee doctor in Kolkata’s RG Kar Medical College and Hospital gains the attention of the public and leads to (sometimes debatable) changes in the law, but the everyday acts of violence faced by women including familial violence, emotional violence, cyber violence and institutional violence largely go unnoticed. I believe that why certain cases of spectacular violence manage to capture collective attention is because of the distance it cultivates with the victim and the distance it cultivates from the act of violence.

This distancing is paradoxical because there is a surge of sympathy for the victim which makes possible public acts of standing in solidarity. It seems that it is easier for us to empathise with a victim who has been annihilated by violence. An absence of speech where we can speak for, insert our indignation, turn our fury, our wrath to the perpetrator. This perpetrator is always an aberration, not someone from our family, not our woke colleague from work who speaks the academic language of feminism and justice perhaps better than us- the perpetrator can never be one of ‘us’.

Perhaps why we think of justice in the case of spectacular violence in the form of another spectacle of violence. A baying for blood, for capital punishment, swift fast-forwarded justice through encounter killings. A reverse shock to dull the infamous ‘public conscience’ back to passivity. The antidote is attentiveness to the everydayness of violence. This is a scary prospect because it reveals to us our complicity in violence. The least tolerant we are thus is of the complaint of the survivor.

Sara Ahmed, feminist writer and scholar famous for coining the term ‘feminist killjoys’ opens her book titled Complaint by writing that ‘To be heard as complaining is not to be heard. To hear someone as complaining is an effective way of dismissing someone’. An alternative to this dismissal according to Sara Ahmed is ‘lending a feminist ear’. Drawing on works of feminists, I add to this building collectives and creating safe spaces.

As I write this Kerala has again shown the long distance it needs to travel in gender equality with the nude clips of actress Divyaprabha from the internationally acclaimed movie by Payal Kapadia ‘All We Imagine as Light’ being circulated out of context. A state that prides in its cinematic literacy, where large crowds flock to watch world cinema at film festivals, a brilliant actress’s sensitive portrayal in a movie of longing and belonging in a migrant city is reduced to a ‘bit piece’ to satiate the sexual frustration of Malayali men.

UN Women has chosen to mark the 25th anniversary of International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women by observing 16 days of activism with the hashtag #NoExcuse. It should be remembered that the UN Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women issued by the UN General Assembly in 1993, defines violence against women as “any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life.” If we have to truly lend a feminist ear to the memory of the Mirabel sisters who were killed by the dictatorial Trujillo regime on whose memory we commemorate the International Day for Elimination of Violence against Women, we will have to look at the everyday violence inflicted on women from an intersectional perspective, no excuse.

Well written article.