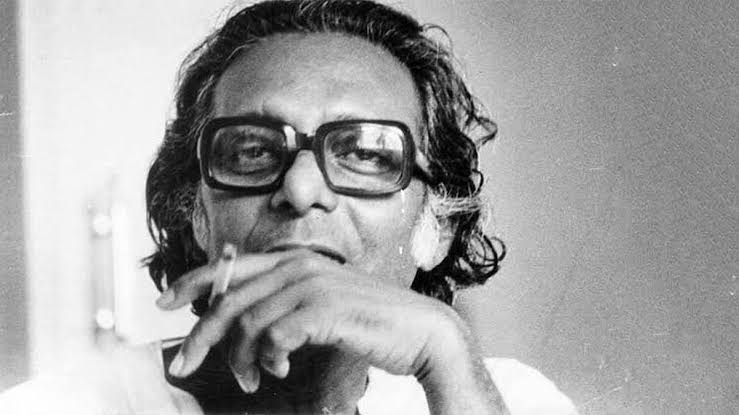

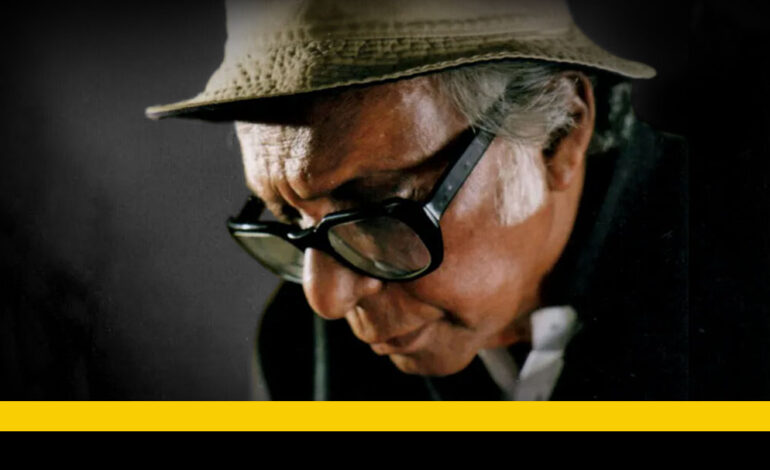

This is the second article in the three part series by academic and film aficionado V Vijayakumar on three masterpieces of Mrinal Sen, a towering luminary in the Indian film world. The films analysed by Vijayakumar are Bhuvan Shome (1969), Akaler Sandhane (1980) and, Ek Din Achanak (1989). The article on Bhuvan Shome was published yesterday. Today Vijayakumar delineates on the cinematic and sociological nuances of Akaler Sandhane.

The AIDEM is presenting this series as a tribute to Mrinal Sen’s unparalleled legacy on the occasion of his birth centenary this year. Sen’s aspiration was to imbue uniqueness and inventiveness into each cinematic rendition. He was a director who constantly experimented and took up every film as a challenge.

Mrinal Da, a proponent of artistic autonomy, navigated diverse routes within parallel cinema. His films unapologetically spoke many tongues. Inspired by Marxism and its artistic perspectives, he ceaselessly sought innovation throughout his cinematic journey.

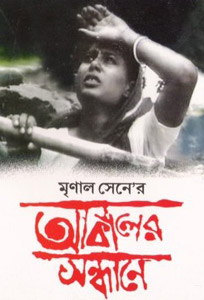

Akaler Sandhane

Mrinal Sen’s ‘Akaler Sandhane’ (‘In Search of Famine’) ingeniously unfolds as a film within a film. The narrative is a film company’s exploration, seeking to depict the harrowing account of the Bengal famine of 1943, a devastating event claiming five million lives. This film within a film carries immense weight, epitomizing Mrinal Sen’s perspective on cinema as a potent medium to articulate and question social realities, challenging his own cinematic ideals. In this project, Mrinal Sen intricately navigates the interface between the movie camera and the harsh reality it endeavours to capture. He handles this delicate thematic territory with great precision, emphasizing the responsibility and sensitivity required when employing the medium of film to shed light on pressing societal issues. This approach in “In Search of Famine” encapsulates Mrinal Sen’s vision as a filmmaker deeply engaged in conveying social truths through his craft, thus positioning his work at the intersection of art, documentary and critical inquiry into the dynamics between cinema and reality.

In this compelling narrative, an aspiring filmmaker, accompanied by his team, descends upon a village and takes up residence in a mansion once inhabited by the affluent Kubera family during the famine of 1943. However, the passage of time has taken its toll, and the mansion now languishes in a state of decay. The village, once witness to the mansion’s glory days, has seen a shift in fortunes. The owners have departed for urban centers like Calcutta, Delhi, Mumbai, or even America, leaving only a woman and her ailing husband in the now-dilapidated mansion. Amidst this socio-economic transformation, an elderly school headmaster recounts the exploitation suffered by the villagers during the historic famine. The wealthy seized land from the impoverished, who, in a desperate quest for sustenance, had fled to Calcutta. Mrinal Sen, the filmmaker, introspectively challenges this narrative. He confronts the harsh reality that, while they document the old famine, a new one is unfolding before their eyes – a humbling moment of self-critique. The filmmaker’s presence in the village, ostensibly to portray a past famine, inadvertently exacerbates the contemporary famine and impoverishment faced by the villagers. The production engenders unintended consequences, sparking complaints that essential local provisions are diverted to serve the needs of the film crew, exacerbating the villagers’ plight. The irony is stark: a film about famine inadvertently creates a famine-like situation for the locals.

Mrinal Sen’s sharp self-reflection underscores a vital lesson for artists – the realization that no matter how committed one is to portraying social reality, artistic endeavors are not exempt from critical evaluation. An artist’s work is not sacrosanct. The narrative exposes the disheartening truth that a society mired in an immoral system diminishes the worth of an artist who remains indifferent to this reality. As the film production presses on, the boundaries blur between past and present, revealing the persistent struggle of rural communities faced with critical food shortages. In Akaler Sandhane the concept of a film within a film, intricately weaves together parallel expressions, intertwining the lives of the characters involved in the film production with the primary theme. Durga, the caretaker responsible for cooking and other tasks for the film crew, finds a connection between her own life and the lead character in the film. Her visceral reaction during a film scene reveals her realization that the cinematic portrayal mirrors her own experiences. The life of the elderly theater actor, an avid art enthusiast, who lends significant support to the film company, becomes entangled with the film’s main theme. His involvement leads him into challenging situations, blurring the lines between art and life. This fusion of art and life is particularly pronounced for individuals like Durga, where the recreated past seems to haunt and resonate in the present. Mrinal Da’s dedication to realism is evident in how he portrays these interwoven stories. Despite employing advanced cinematic techniques, he firmly retains his commitment to realism, emphasizing that film as an art form should primarily reflect reality. He thought that film art should be seen first and foremost as a realistic art form.

As the narrative unfolds, an actress departs for Calcutta, prompting the team to search for a replacement to portray the village prostitute. This quest leads them to the local village, attempting to find a suitable candidate for the role. In the pursuit of finding a suitable actress to portray the village prostitute, the film crew encounters a village headman’s daughter, who aspires to be an actress. However, upon learning of the intended role, the village headman vehemently opposes the idea, fearing the societal repercussions and the potential labeling of his daughter as a prostitute.

This incident prompts reflection on the intricate relationship between art and life. The village Headman’s perspective highlights a vital aspect – art is life itself. But more than that, art is art. Film can be an expression of life. But for the first time, it is the film itself. The filmmaker, in his dilemma, explores approaches that challenge traditional artistic norms and beliefs. Here we meet the filmmaker who is eager to say that there are instances where art needs to be separated and examined, from life. It underscores the notion that while art can mirror life, it can also deviate from reality, presenting situations that demand scrutiny and separation from the lived experience. Mrinal Sen’s staunch adherence to Marxism and its views on art didn’t inhibit his creative exploration; rather, it fueled a relentless drive to critique and self-critique. This critical stance propelled him to constantly seek and experiment with new film techniques, challenging conventional and mechanistic interpretations and affirming that art, although intertwined with life, maintains its unique essence and should be examined on its own terms.

The film crew’s search for an actress leads them to Durga, a woman grappling with the burden of caring for her ailing child and disabled husband. Their survival depends on the fruits of her labor, and the money she could earn from acting in the film would have alleviated their struggles. However, the circumstances are not favourable, and Durga is compelled to repay money she had borrowed for her son’s medical treatment, because her husband objects. Discontent brews within the villagers against the film crew, further exacerbating tensions. On the advice of the headmaster, sensing the growing discord, the film crew decides to leave the village. Mrinal Sen concludes the film delving into the remaining trajectory of Durga’s life. Tragically, the infected child succumbs to the disease, and Durga’s husband departs, leaving her utterly alone. The audience is left with a poignant realization—that those who barred Durga from art, inadvertently excluded her from life as well. Mrinal Sen skillfully underscores the intricate and often precarious relationship between art and life in this film. In effect, this conjunction deftly problematizes the perennially uncertain and ambiguous correlation between art and life.

Part 03 focusing on Ek Din Achanak released in 1989 to follow. Stay Tuned.

To receive updates on detailed analysis and in-depth interviews from The AIDEM, join our WhatsApp group. Click Here. To subscribe to us on YouTube, Click Here.

Vijayakumar’s analysis of Mrinal Sen’s work is competent but not comprehensive enough . Sen’s Marxist orientation should have been dealt with at greater length . Here , we only see passing references .

Thanks for the this valuable comment.

We should explore more.