Urban Acupuncture: Lessons from Curitiba, Brazil

In 1993, I met the American environmentalist Bill McKibben and his family in Curitiba, Brazil when I was a Masters student from the University of California, Berkeley, interning for three months at the Institute of Urban Planning and Research. I knew he was pursuing ‘success stories’ and he was as surprised to hear of my Kerala roots as I was to hear that his next stop was Kerala! A year later, he sent me a copy of his book – ‘Hope, Human and Wild’ which featured both Kerala and Curitiba, as examples of ‘living lightly on the earth.’ Bill has since gone on to become the foremost environmental campaigner in the US, leading a global climate campaign called ‘350 Degrees’ and also winning the Gandhi Peace Award in 2013. So, why did Bill find Curitiba worth talking about? And what can Kerala, whose development model and social and educational indicators are the envy of other Indian states, learn from the city of Curitiba? Just what is so special about this Brazilian city?

When you first encounter it, Curitiba seems like a first world city, not a Brazilian city. Everything seems carefully designed – beautiful bus stops, the ‘pine cone’ inspired zebra crossings, streets with good signage, lots of public parks with low garden lamps, a pedestrianized downtown and a beautiful, historic city centre with cafes and museums and art galleries. Located south of Sao Paulo, Curitiba is the capital of the state of Parana, with a population of 2 million. It has won many awards globally and is considered by top urban planners to be one of the most livable cities in the world today. Brazil’s ecological capital, Curitiba recycles 70 percent of its waste. Like Kerala, it tops various social indicators in Brazil, but unlike Kerala it is also low on unemployment.  This success story was due to a planning turnaround that started in the 1970s, when it was struggling like other cities in Brazil to manage traffic congestion, flooding, pollution, lack of housing, and sanitation. But over the next twenty years, it was transformed into one of the most livable cities in the world through a series of creative experiments by its architect-mayor Jaime Lerner (over his three terms as mayor) and his talented team. Even more surprising, this turnaround came about despite not having much money at its disposal. So how did Curitiba manage to achieve this remarkable transformation? I will outline below a few key principles and initiatives which are relevant to consider in developing our own solutions.

This success story was due to a planning turnaround that started in the 1970s, when it was struggling like other cities in Brazil to manage traffic congestion, flooding, pollution, lack of housing, and sanitation. But over the next twenty years, it was transformed into one of the most livable cities in the world through a series of creative experiments by its architect-mayor Jaime Lerner (over his three terms as mayor) and his talented team. Even more surprising, this turnaround came about despite not having much money at its disposal. So how did Curitiba manage to achieve this remarkable transformation? I will outline below a few key principles and initiatives which are relevant to consider in developing our own solutions.

Creative solutions: Urban Acupuncture

Curitiba is known as the city which gave the world the Bus Rapid Transit System (BRTS). Today, it is also the city with the most per capita open space in the world (55 sq m of open space per person) though it started with less than 1 sqm per person in 1970. A lot has been written about its transportation innovations, though there is not much on all the other innovations that mark this remarkable city. A unique approach to problem solving marks all of Lerner’s solutions which he called ‘urban acupuncture.’ Problems are of course inter-related. He believed that ‘in urban planning it is also necessary to make the city react; to poke an area in such a way that it is able to help heal, improve, and create positive chain reactions…..” What marks all of Curitiba solutions is that there is a convergence approach to problem solving – so every solution is necessarily addressing more than one problem at the same time. Problems are approached as opportunities for change.  Each problem is broken down and intimately understood so that an apparently big problem is broken down into smaller ones that are easier to solve. Also, the solutions are very contextual and directly address the real issues on the ground. At the core is a people-centric approach with design being a key input in all the solutions. Unlike in India, where there is typically no institution at the city level to conduct research or enable plan implementation, Curitiba set up an Institute of Urban Planning and Research in 1970. With an interdisciplinary team including sociologists, economists and engineers and a hundred architects primarily to support the planning team with research, documentation and design of actual projects, it ensures that solutions are developed from sound research and plans get implemented properly. It was at IPPUC that Lerner started as Director to first concretise the details of the plan on the drawing board before he took over as Mayor and oversaw project implementation.

Each problem is broken down and intimately understood so that an apparently big problem is broken down into smaller ones that are easier to solve. Also, the solutions are very contextual and directly address the real issues on the ground. At the core is a people-centric approach with design being a key input in all the solutions. Unlike in India, where there is typically no institution at the city level to conduct research or enable plan implementation, Curitiba set up an Institute of Urban Planning and Research in 1970. With an interdisciplinary team including sociologists, economists and engineers and a hundred architects primarily to support the planning team with research, documentation and design of actual projects, it ensures that solutions are developed from sound research and plans get implemented properly. It was at IPPUC that Lerner started as Director to first concretise the details of the plan on the drawing board before he took over as Mayor and oversaw project implementation.

Waste as a Resource: Food for Garbage Programme

Cities of the global south routinely fail to manage their garbage – solid waste – properly. However, Curitiba started waste segregation in the nineties. Awareness is key to ensure that people do segregate waste at source. So, awareness programs were conducted through schools using newly-created cartoon characters- the Leaf family! Soon school going children were made primarily responsible for segregating waste in their homes. Enthusiastic kids carried this message home and also formed a future citizenry that was environmentally aware. However, the problem of uncollected garbage from the slums in the city still remained unresolved. This garbage invariably ended up in drains and water bodies, along which these settlements are often located. The municipality made repeated attempts to get the slum dwellers to collect and dispose off their waste through the municipal collection system, but it was not very successful. They even tried offering incentives in the form of bus tickets, to no avail. However, an opportunity presented itself through a glut of oranges in the orange farms around the city. Farmers were simply throwing away rotten fruit, without being able to sell at a decent price. Lerner, who was mayor then, felt that he had to find a solution to this mindless waste of fruit on one hand and poor hungry families on the other. He decided that the municipality should intervene. So, they stepped in, bought the fruit from the farmers and offered it to the slum dwellers, bartering in return for their garbage. This was successful and soon gave rise to the ‘Food for Waste’ program of the municipality. slum communities got organized so that a list of households was prepared and the garbage truck would arrive bearing a weekly ration of balanced food for every kilo of garbage handed over. Suddenly slums were clean, healthy food was available to poor families and the overall health of the slum residents improved, with just a powerful idea of offering balanced food packets in exchange for garbage. Today Curitiba has a seven-bin segregation system and continues refining the exchange program to include school books at the beginning of the academic year or other incentives to slum dwellers.

Parks: What do open spaces have to do with flood control?

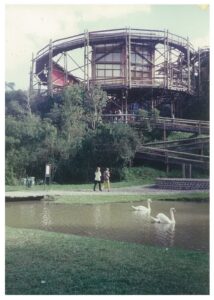

In the seventies, Curitiba faced annual flooding due to the five rivers that ran through the city. Again, Lerner and his team had an interesting response. Federal funding was available for channelizing these rivers to resolve this problem. Instead of using hard engineering, Lerner used the funds to acquire all the private land in the flood plains of the rivers and converted into parks. Additionally, holding ponds in the form of lakes, were created to store the flood waters. The master plan ensured that peripheral floodplains converted into regional parks.  The river courses were thus integrated into a network of parks across the city and smaller neighbourhood parks were also created all across the city. Alongside, from Lerner’s first term in office, afforestation was a key strategy. Citizens were played an active role in greening the city, and they were given saplings to plant and water. Over time, the park system was also strengthened with separate bike trails. Wetlands were developed along the water bodies, to also help with sanitation. Once again, design is an integral part of the process. However, the best part of the story is how the municipality manages the maintenance of these parks that it has created, given its lack of funds – it employs a single shepherd and a flock of thirty sheep who move from park to park throughout the month!

The river courses were thus integrated into a network of parks across the city and smaller neighbourhood parks were also created all across the city. Alongside, from Lerner’s first term in office, afforestation was a key strategy. Citizens were played an active role in greening the city, and they were given saplings to plant and water. Over time, the park system was also strengthened with separate bike trails. Wetlands were developed along the water bodies, to also help with sanitation. Once again, design is an integral part of the process. However, the best part of the story is how the municipality manages the maintenance of these parks that it has created, given its lack of funds – it employs a single shepherd and a flock of thirty sheep who move from park to park throughout the month!

Transport: Can Private Buses be mobilized to create an integrated system and replace a Metro?

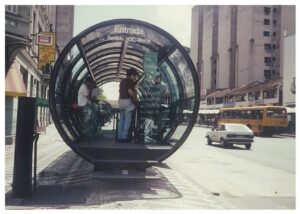

Just as in Kerala, bus transport in Curitiba was and continues to be provided by private bus operators. The municipality negotiates with the contractors and pays a fixed amount per kilometer for the service offered. The daily collection is turned over to the municipality. A single fare is set regardless of distance travelled. This means that the poor who live farther away from the city centre are cross subsidized by the rich who live closer. Dedicated bus lanes introduced in the 70s meant that bus transport was fast and became the preferred mode of transport. Today, 80 percent of all travelers use the bus. Lerner and his team proposed a master plan which had at its core an integrated mass transport bus system. Five linear transport axes were proposed that transformed the radial concentric structure of the city into a more linear one, along these axes. Dedicated bus lanes were created to enable faster movement of people. By providing a dedicated bus, they improved the speeds for bus travel and made it a preferred mode. Additionally, instead of one wide road, (which would mean demolition and loss of property) they pushed for narrower streets working together as a trinary system: 2 one-way streets and one central BRT corridor. In time, they introduced synchronized signaling to ensure that the light at every signal stays green for buses as they run, much before this became commonplace world over. A decade later, when the buses became overcrowded, they redesigned the bus. They created bi-articulated and later tri-articulated buses to increase the capacity of the bus itself so that a single bus would hold 270 people. Also, to increase travel speed, they kept innovating – to reduce boarding and alighting time they created the now-iconic raised tubular bus stops which people entered by paying the tickets like at railway stations. This saved boarding time, because buses earlier had meters at the entrance which created delays. Also, the bus stops have been designed with hydraulic lifts to enable access to wheelchairs and prams.

In time, they introduced synchronized signaling to ensure that the light at every signal stays green for buses as they run, much before this became commonplace world over. A decade later, when the buses became overcrowded, they redesigned the bus. They created bi-articulated and later tri-articulated buses to increase the capacity of the bus itself so that a single bus would hold 270 people. Also, to increase travel speed, they kept innovating – to reduce boarding and alighting time they created the now-iconic raised tubular bus stops which people entered by paying the tickets like at railway stations. This saved boarding time, because buses earlier had meters at the entrance which created delays. Also, the bus stops have been designed with hydraulic lifts to enable access to wheelchairs and prams.

The Ecological City: Recycle, Recycle, Recycle

Since the nineties, in Lerner’s last term as mayor, the environment was a central focus along with creating a city as a ‘space for encounter’. Recycling became a key strategy in achieving these twin aims. Along with the segregating of garbage, afforestation and the creation of more and more parks, quarries were now recycled to create a range of public spaces including the Opera Arame, a wire-frame opera house (built with recycled materials in 60 days), an amphitheatre for rock concerts, an Open University for the Environment (from recycled telegraph poles) and public parks. A landfill site was recycled to become a Botanical garden while a central street was converted into a 24-hour Street, to create a vibrant public space in the city. Older low floor buses (retired after ten years) were recycled for various purposes including mobile training schools while beer bottles were recycled as park lamps, with their tops lopped off.

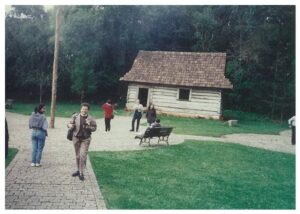

There are many more interesting stories and successful projects from Curitiba including how the city’s historic core was saved and its community museum, the ‘House of Memory’ set up with personal family stories from citizens or the 5000-book neighbourhood libraries -‘Lighthouses of Knowledge’- that light up at night and offer much needed security on the street. The examples are many but they all carry a germ of how to think about solutions for our cities too.

Effective and elegant because Sustainable and Local

What each of the above examples from Curitiba tells us is that Kerala too needs to question every one of the high-cost ready-made solutions on offer, be it the metro, the K-Rail, the bullet train or the Smart city. Each of these are in fact a solution in search of a problem to be solved. Instead, home grown solutions, that count on people, that are low-cost, and address many problems at once, would be the way forward. As Lerner famously said, “If you want creativity, cut one zero from your budget. If you want sustainability, cut two!”