“Dard”: On the Footsteps of a Poet Who Called Himself Pain

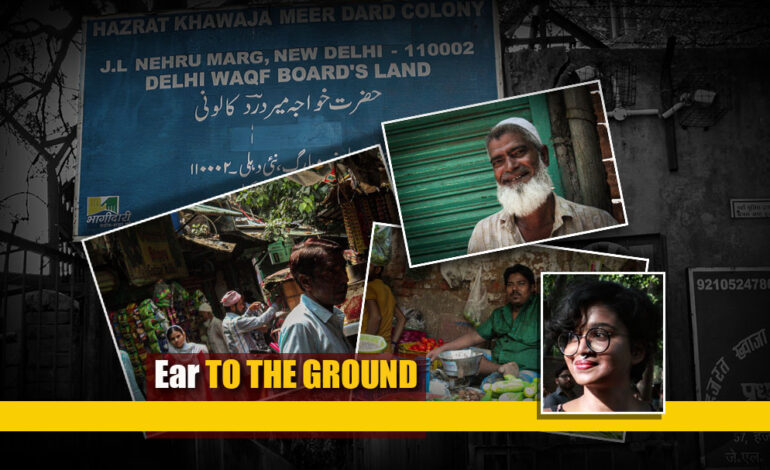

Ear to the Ground is a special feature by The AIDEM that reports on offbeat field reports on people’s lives and livelihood issues. “Dard”: On the Footsteps of a Poet Who Called Himself Pain” is a ground report by Devangana Rajeev after a photo walk in the Hazrat Khwaja Mir Dard Colony.

“In times of crisis, poetry always plays the role of a documenter. When the words fail to capture the silences of human tragedy; when the numbers can’t quantitatively reach the bottom of human hearts; the scattered words are picked up by poets to weave the dreams of a new world.” This was written by journalist Shreya Basak in an article about the 2016 Kochi-Muziris Biennale, which focused especially on one of the installations in the exhibition that saluted the memory of Aylan and Galip Kurdi brothers, the Syrian refugee children aged 3 and 5 who died on the Turkish coast of the Mediterranean Sea in 2015 while trying to cross the sea and seek refuge in Europe. The tribute to the brothers was by Chilean poet Raul Zurita, whose lines read thus: “…Below the silence you can make out a piece of sea, of the sea of pain. I am not his father, but Galip Kurdi is my son.” What Zurita had captured as a poet and what Basak had recorded as a journalist were essentially the same thing; the pain of the refugee.

“Delhi which has now been devastated,

tears are flowing now instead of its rivers”

I had not read Zurita or even Basak, when I walked out of my college one hot afternoon and sauntered into a congested alley inside a gate just next to the college. The alley was sandwiched between two big institutions: the Zakir Hussain College and the Dr. Shyama Prasad Mukherjee Civic Centre, which is considered to be one of the tallest government buildings in the national capital of Delhi. It was lunch time, I was hungry and I had heard from my friends about the non-vegetarian delicacies that the alley offered; the kormas, biryanis and kebabs of different types of meat and the hot rumali rotis. I had also slung my camera on my shoulders as I had an inkling that the alley would give me some nice or interesting shots of people and life.

I started walking through the narrow road of the basti. I saw a group of youngsters excitedly preparing roti. Their faces were glistening with sweat from the heat of the burning fire in the nearby stove. A thin, bald boy, whom everybody called by the name of Chottu, (literally a little boy) was eagerly serving roti and meat to those who had come to eat. A group of women were engaged in household chores around the roti joint and were scattered widely. In the dazzling sunlight, their eyes glittered under the hijab like black pearls. A little further away I saw another set of women begging in the corner of the street. The numbness that life imposed on them was sought to be carefully hidden under their hijabs. Yet, the ‘pain’ in their eyes was caught by my “photographer-eye” and the painful expression pierced me like a sharp needle.

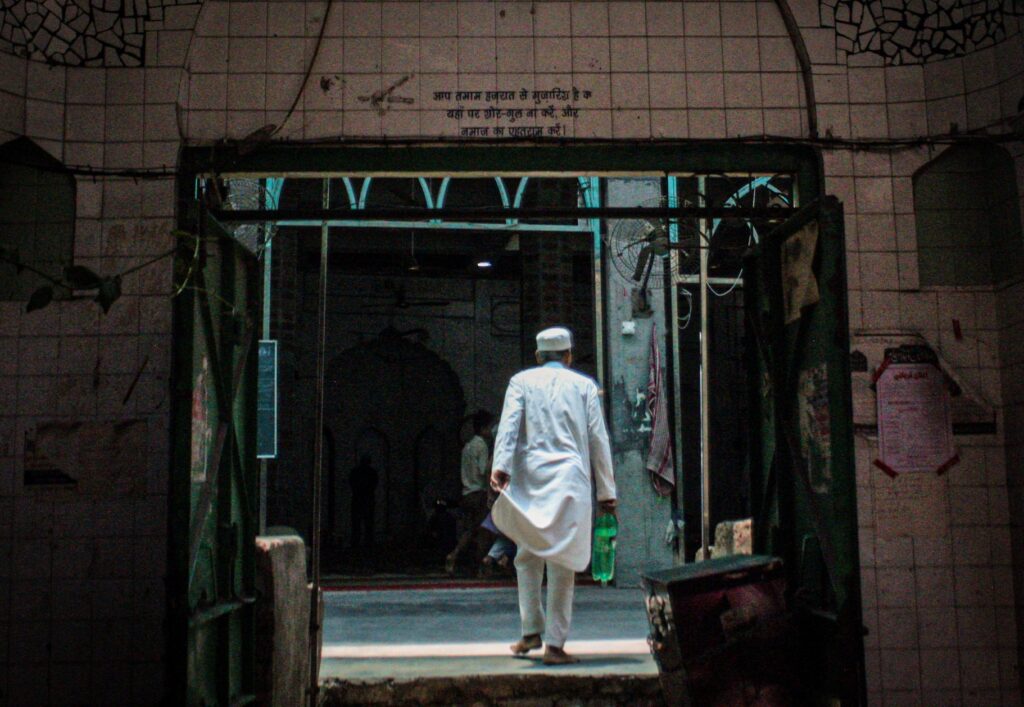

No change from outside seemed to have penetrated into this gully for decades, just as sunlight does not penetrate into a dense jungle. But, like every other dwelling place of people, there was a hustle and bustle generated by everyday life. Amidst this, the ‘Azaan’ was heard from a small mosque nearby. It was a beautiful, evidently sacred meditative looking space in the midst of the cramped, crowded street. Its walls seemed to be covered by a pale green coat of innocence. Soon, old men in white garments flowed into the mosque. After praying, people returned to their homes. The mosque was located among an array of congested little shops.

I wandered through lanes and bylanes and once again came back to the entrance. It was then that I saw the board: “Welcome to Hazrat Khwaja Mir Dard Colony”, the old blue board stood up in the scorching summer heat as if in defiance to the rest of the world. Indeed, the name of the colony intrigued me. I knew what “dard” meant in Hindi and Urdu. Pain. Why would a colony name itself as pain? I asked some men and women, who did not appear to be too busy and were standing around in a leisurely manner. What they told me was even more intriguing. The colony was named after Hazrat Khwaja Mir, the legendary Urdu Sufi poet, who named himself “Dard”; pain or sorrow. He apparently lived in these parts of Delhi in the 18th century.

The alley and the life there suddenly became even more interesting for me. I went back there again and again. In a sense, it was as though the colony was drawing me like a magnet. Soon, I was not a new visitor there. Few people started recognizing me. I roamed there repeatedly. I got adjusted to the unsanitary environment. The small population living in it had become familiar to me. But, the trigger to these familiarising journeys was the curiosity about a man who called himself “Dard”.

Later, while talking to a group of women, one of them said that the poet must have named himself “Dard” looking at the lives he and his compatriots lived in the colony. She went on to add that almost all of them have very cramped, meagre existence. “We live in the same room, sleep on the same floor, eat the same food. From the outside, no one would realise that such a colony existed in between two tall, historic buildings. But then, here we are. The children of Dard”. The woman too seemed to turn poetic.

I started researching on Hazrat Khwaja Mir Dard and found that he had written these lines : “Our hearts and breasts are selling the roses of the scar of friendship. Our shop does not contain anything except pain”. Sufism scholar Annemarie Schimmel, wrote extensively about Dard in her book, “Pain and Grace: A study of two mystical writers of Eighteenth century Muslim India”. The book, published in 1976 vividly described the life of Mir Dard and the condition of Delhi during that time. The 18th century is usually considered to be the time of lowest ebb for the islamic people between the Balkans and Bengal. Dard’s own life had some reflections of the tumult happening in that society at that point of time. Initially, he became a soldier to make a living but found it hard to adjust to that life. He left the profession and joined the monastery of his father.

Mir Dard is one of the three major poets during that period – the other two being Mir Taqi Mir and Mirza Sauda, who could be called the pillars of the classical urdu ghazal. While Mir Taqi Mir is remembered as the poet of love and pathos, and Sauda as a specialist in satire and panegyric, Dard is first and foremost a mystic who regards the phenomenal world as a veil of the eternal reality and this life as a term of exile from our real home. Through his poems, he expressed his feelings for others. He once wrote: “ I can break the promise that I have given to God, but I cannot break the hearts of people”. He was a poet of humanity and Tasawwuf, which means being a sufi. He believed in the power of human deeds. Schimmel points out that the secret of Dard’s appeal as a poet lies not in his mysticism, but in his ability to transmute this mysticism into poetry, and to present transcendental love in terms of human and earthly love. Although he has written ghazals which are unambiguously mystical in their intent, his best couplets can be read at both the secular and spiritual level, and are for this reason, acceptable to all and sundry. In other words, Dard wrote about eternal reality and human pain. For him the ‘pain’ is eternal.

As I spent more and more time in the colony, I realised that the name of the place as well as the poet who lived there were historical allegories that transcended generations. Dard was there everywhere in the basti, inside and outside. Too many lives in a very congested area including a variety of animals including horses, goats and chickens. There was a strange intensity in the eyes of men and women, which had shades of despair. The crumbling walls of houses and buildings had a lot to tell, some with spots, some patchy with faded colours. Those walls were plastered long ago. No one bothered to fix it later. Dilapidated buildings could be seen everywhere. But there seemed to be no attempt to renew or rebuild any of them.

But the inner by-lanes of the gully were filled with aromas of hot rumali roti, simmering meat kurma, hot chole bhature, mutton biryani and so on.The fruit vendors tried to keep their mangoes and bananas fresh though their faces were wilting in the oppressive summer. Children were playing with goats, completely ignoring the torrid summer heat.

Significantly, the poet never left Delhi in spite of all the misfortunes that came over the city during his lifetime. The political turbulence and the natural afflictions were such that it triggered a movement among most of the poets, musicians and scholars to wander East in search of livelihood. Dard however, continued his preaching, writing, listening to mystical music and instructing poets. He wrote: “Delhi which has now been devastated, tears are flowing now instead of its rivers”.

Not surprisingly, the major landmark of the basti is the memorial tomb of the poet. The dargah inside the basti is old, and had been there long before India’s Independence. The faded colours on the walls of dargah themselves told a gloomy story of successive eras. After Independence people slowly started settling in the surroundings of dargah. The dargah was the chief attraction for people from Uttar Pradesh and Haryana to come and settle here. In 1947, the 25 acres land around the dargah was a graveyard. Initially, the settlements were small but in the last five decades it increased and the number of residents burgeoned. Since the early 1990s, many of the residents told me, more and more people have come here from places like western Uttar Pradesh looking for a place to stay. Perhaps they got a sense of solace, being in the surroundings of a place where a poet who identified himself with pain lived.

But beyond that solace, these residents assert, getting together among the brethren in the colony gives a sense of relief and security too, because of the insecurity that is spreading on across the society on account of different things including suggested amendments to citizenship laws. “Is it not a sort of ghettoization that was happening here?”. I asked a few people, including some families. A wry smile was the only answer I got. Were they pretending to act as though the harsh reality of the outside has not yet penetrated the walls of the colony?

Annemarie Schimmel had written that “the history of Indian Islam is not only a history of political facts, of conquests and wars, of expansion and breakdowns, but a spiritual history as well.” There may be a lot of unknown history in the basti, but no matter how much time has passed, what remains unchanged is ‘dard’, the ‘pain’. While coming back through the narrow road of the basti, the last line of Auden’s poem “The Unknown Citizen” flashed through my mind: “Was he free? Was he happy? The question is absurd: Had anything been wrong, we should certainly have heard”.

Ear to the Ground is a special feature by The AIDEM that reports on offbeat field reports on people’s lives and livelihood issues. Read previous reports here.

“Had anything been wrong, we should certainly have heard”.💔

Beautifully written , with evocative pictures The pain of the poet and the colony comes out through this portrayal . Thank you

😌👌

A good mix of facts found through great research and interaction, with reflections of the author. Glad that I came across this piece of work. Thanks @Devangana!!

Amazingly written article with appealing pictures . I have also seen this colony and wanted to know about it. Thanks for choosing such a beautiful topic to discuss.

❤️