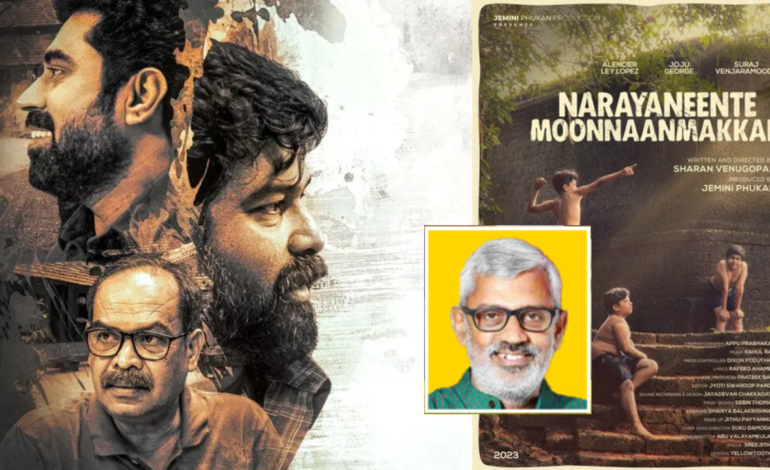

There are films that unsettle, not because they shock, but because they hold up a mirror to the hidden fractures within human relationships. Narayaneente Moonnaanmakkal, the debut feature by Sharan Venugopal, is one such film—an unflinching exploration of what is dubbed as incestous relationship, not through the lens of provocation, but with an unwavering commitment to human truth. While its theatrical run was largely overlooked, its arrival on Amazon Prime has begun to stir conversations, drawing attention to its stark and uncompromising narrative.

(Though the film may evoke echoes of works by Pedro Almodóvar, Bernardo Bertolucci, and Michael Haneke, this is not to suggest imitation or direct comparison. The references arise organically, placing Narayaneente Moonnaanmakkal within a broader cinematic discourse.)

Cinema has long wrestled with the complexities of human relationships—the unseen tensions, the unspoken betrayals, the fragile fault lines that exist even in love. Venugopal embeds this unsettling theme within the rhythms of a hyperlocal world, its language and setting deeply rooted in the Koyilandy dialect. Yet, despite its regional specificity, the film transcends boundaries, embodying the quiet evolution of contemporary Malayalam cinema—one that dares to tell difficult stories with uncompromising honesty.

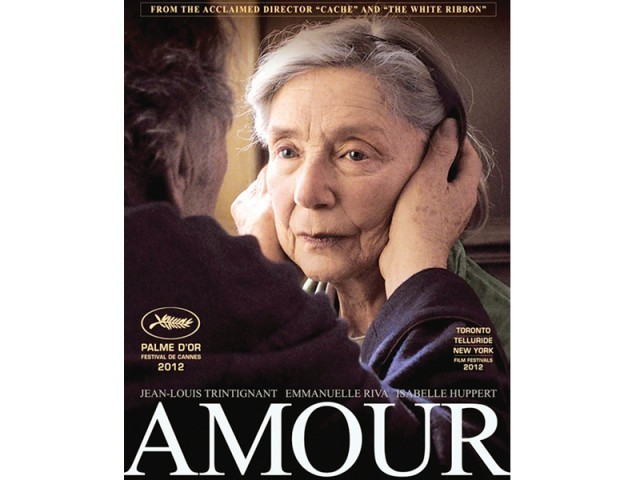

In many ways Narayaneente Moonnaanmakkal treads the same haunting terrain as Michael Haneke’s Amour (2012). Both films strip relationships down to their bare bones, leaving behind more questions than answers. In Amour, a daughter recalls the moment she accidentally witnessed her parents in an intimate act—not with shame or discomfort, but with a quiet realization of life’s fragility. Convention dictates that such moments are to be erased, silenced, deemed improper. But Haneke refuses such moral policing, forcing us to confront our deeply ingrained hypocrisies—our tendency to label nature as unnatural, to turn love into something shameful, to mold morality into a rigid, unforgiving structure.

Perhaps the most devastating moment in Amour is when Georges, weary of watching his wife suffer, smothers her with a pillow. Not out of cruelty, not out of malice, but out of sheer helplessness. Even death, the film seems to suggest, does not come easily. The horror lies not in the act itself, but in the unbearable weight of inevitability.

A similar moment unfolds Narayaneente Moonnaanmakkal. Bhaskaran, anxious to return to London, attempts to suffocate his bedridden mother, desperate to free her—and himself—from an existence suspended between life and death. His brother, watching from behind, confesses that he too had tried and failed. There are no explanations, no justifications—only the quiet, terrifying truth of what people do when left with no way out.

Bhaskaran and his family return to Kerala, summoned by their eldest brother, in what they believe will be a reckoning, a closure. But wounds, even when they seem to heal, leave behind deeper scars. The past does not simply dissolve. And in trying to bury it, they only unearth more pain.

Vishwanathan, who once attempted to end his mother’s life but failed, is the same man who is enraged when he sees his daughter, Aathira (Gargi Ananthan), in love with Bhaskaran’s son, Nikhil (Thomas Mathew). This selective morality—choosing principles that suit one’s convenience—becomes the foundation of his character, much like the recent trend in Malayalam cinema that revolves around selective amnesia.

Pedro Almodovar’s Talk to Her (2002) presents a male protagonist who navigates isolation, love, and obsession, echoing themes of solitude and longing. Almodovar often explores narratives that challenge moral absolutism and rigid societal constructs, bringing his characters into the forbidden corners of human desire and ethical ambiguity.

The film revolves around two primary male characters—Marco (Darío Grandinetti), a writer, and Benigno (Javier Cámara), a nurse. Their lives intersect when they both witness a ballet performance. Marco, overwhelmed by emotions, sheds tears, unaware that Benigno observes everything. Their paths cross again at a hospital, where Marco’s lover, Lydia (Rosario Flores), lies comatose after a bullfighting accident. Benigno, who works at the hospital, takes care of Alicia (Leonor Watling), a young dancer also in a coma after a car accident. His attachment to her borders on obsession; he had secretly admired her from his apartment balcony long before fate placed her under his care. Cinema, after all, is the art of voyeurism, of watching without being seen.

As the film progresses, it unveils the intricate layers of human emotions, ethical dilemmas, and relationships. Lydia’s past resurfaces—her former lover had rekindled their romance just before her accident. Marco, feeling betrayed, leaves for Jordan, unable to reconcile love with the weight of infidelity. The film asks unsettling questions: Can love persist after betrayal? If a lover falls into an unconscious state, how does one grapple with unresolved emotions? And if a former partner reclaims their love but refuses to care for them in their helplessness, does that mean their love was only for the conscious, present self?

Benigno, on the other hand, takes his connection with Alicia to an unspeakable level. When doctors discover that she is pregnant, they realize he has violated her in her comatose state. He is imprisoned for sexual assault, his actions a horrifying blend of twisted devotion and moral transgression. Meanwhile, Alicia miraculously regains consciousness after childbirth, raising an unsettling paradox—her rebirth into life was triggered by the very man who destroyed its sanctity. The legal and ethical quagmire that follows is classic Almodóvar—a civilization confronted with its own contradictions. Marco, unaware of Alicia’s recovery, is prevented from informing Benigno, fearing his reaction. Ironically, Benigno, convinced he will never be reunited with Alicia, ends his life.

At its core, Talk to Her is a meditation on loneliness, love, and the invisible lines between care and obsession. Almodóvar crafts a world where conversations—both spoken and unspoken—define the essence of human connection. The film lingers as an uneasy yet profound exploration of intimacy, loss, and morality, refusing to offer easy resolutions.

This theme of love, longing, and the fragile nature of human connections resonates in Malayalam cinema as well. Much like the characters in Talk to Her, Aathira and Nikhil in Narayaneente Moonnaanmakkal grapple with isolation and rejection. When love becomes their refuge, should they be condemned for finding solace in each other?

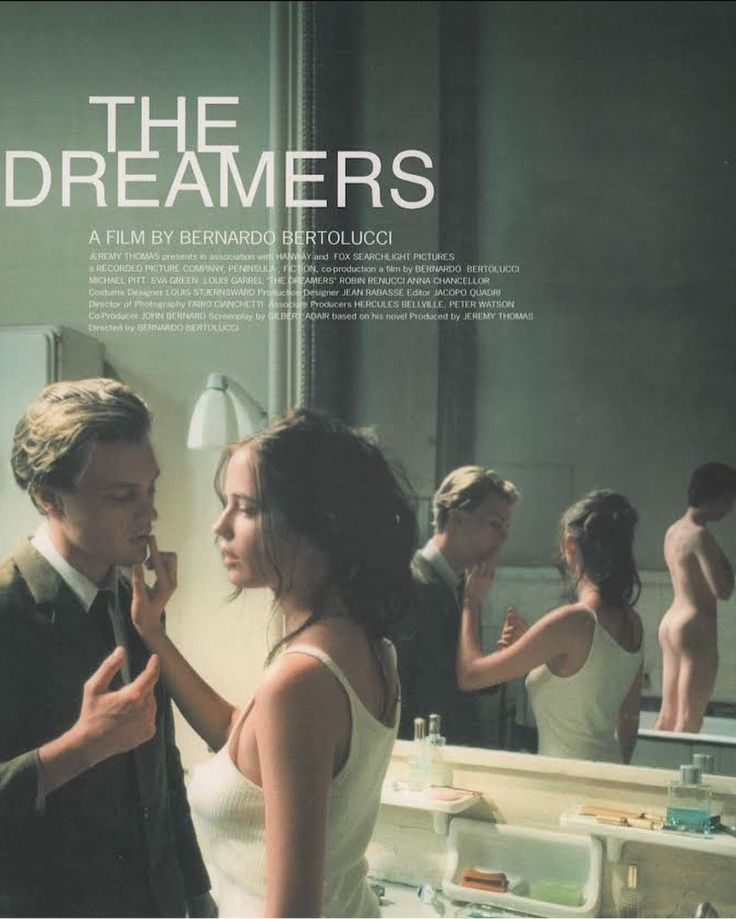

Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Dreamers (2003), adapted from Gilbert Adair’s The Holy Innocents (1988), delves into a world of intense passion, youthful rebellion, and the convergence of cinema and revolution. The film portrays its characters as simultaneously fragile and audacious, driven by desire yet anchored in naiveté. Bertolucci masterfully entangles love, politics, and art, crafting an evocative portrayal of youthful idealism clashing with harsh realities.

Mathew, an American cinephile, arrives in Paris with one singular obsession—to immerse himself in the world of cinema. He religiously secures a front-row seat at every screening, believing that the farther one sits from the screen, the more diluted and fragmented the cinematic experience becomes. To him, a film’s essence is best absorbed from the closest vantage point. The pioneers of the French New Wave—Godard, Chabrol, and their contemporaries—shared this fervor, claiming the front rows of Cinematheque Francaise, the temple of cinephilia curated by Henri Langlois. When the government shut it down and arrested Langlois, a storm of protest erupted. Truffaut, Godard, Rivette, Rohmer, and Chabrol were not alone in their resistance; titans like Chaplin, Rossellini, Fritz Lang, Carl Dreyer, and Orson Welles stood in solidarity. The police retaliated with batons, injuring even Godard—a fitting metaphor for the bruises that authority inflicts upon artistic rebellion.

In this pulsating city, Mathew encounters Theo and Isabelle, enigmatic twins whose bond is as intoxicating as it is unconventional. Drawn into their orbit, he abandons his hostel room and moves in with them, surrendering to a labyrinth of psychological, physical, and erotic entanglements. Their relationship defies categorization—at once profound and unsettling. When their parents witness the tangled intimacy that has unfolded in their absence, they say nothing, choosing instead to walk away, helpless and silent.

Though Mathew is consumed by his love for Isabelle, she ultimately leaves him behind to join the student revolution of May 1968, hand in hand with Theo. The rupture is not just personal but ideological. Mathew, an American accustomed to the apolitical comfort of detachment, is at odds with the feverish political consciousness of the French. While he seeks solace in film, Theo and Isabelle awaken to the urgency of the streets. Even in matters of war, they are irreconcilable—Mathew’s indifference toward Vietnam clashes with Theo’s impassioned resistance.

Bertolucci’s The Dreamers is not just a film; it is a love letter to cinema, an intricate tapestry where celluloid and life blur into one. Every gesture, every dialogue, every fantasy of its characters echoes moments from film history—scenes lifted from Godard, Truffaut, Chaplin, and Browning, woven seamlessly into the narrative. The characters, like Bertolucci himself, live through the films they worship. They debate the artistic genius of Buster Keaton versus Charlie Chaplin with the intensity of theologians arguing over scripture. Theo and Isabelle’s father, a celebrated French poet, exists in stark contrast to the primal, visceral energy of his children. “A filmmaker is nothing but a voyeur,” the characters muse, quoting Cahiers du Cinema. Bertolucci, with disarming self-awareness, likens the filmmaker’s lens to a child peering through the keyhole of his parents’ bedroom. Love, he suggests, does not exist—only the proof of love does.

Amid the smoldering unrest of 1968, Bertolucci poses an aching question: Can love, desire, dreams, and cinema offer a refuge when revolution rages in the streets? Theo and Isabelle are like conjoined twins, severed yet inseparable, mirroring the still from Bergman’s Persona that lingers on their desk. Are they two souls or one fractured into halves? Their characters expose the collision of sexual impulses, longings, and contradictions within a single self. This is why Mathew’s love for Isabelle is both desperate and doomed—his plea, “I want only your love,” is a plea against an impossible reality.

The youthful idealism of the 1960s, with its revolutionary fervor and its radical reimagination of love, morality, and art, is the lifeblood of The Dreamers. Bertolucci himself admitted that his film was fueled by his own utopian desires—for political rebellion, for cinematic purity, for the subversion of social order.

This same unease with traditional structures runs through Narayaneente Moonnaanmakkal. The film unearths the discomfort that arises when societal norms are disrupted—especially those governing love and relationships. The intimacy between Aathira and Nikhil, cousins by birth but lovers in spirit, unsettles audiences. But is it truly a transgression, or is the discomfort merely a conditioned response to an age-old construct? The film poses a challenge: In a land where cousins are often betrothed without question, why is this particular love viewed as unnatural? Tamil Nadu normalizes marriages between maternal uncles and nieces, yet Kerala recoils at the idea of cousins choosing each other. If the justification is biological, where is the scientific proof of inherent harm? The unease is not rooted in genetics but in centuries of ingrained propriety.

The same oppressive structures that condemn Aathira and Nikhil also dictate Bhaskaran’s fate. His love for Nafeesa, a Muslim woman, is a battle he is never meant to win. Even in the so-called modern age, interfaith marriages remain acts of defiance, challenged by the same archaic forces that disguise prejudice as tradition. Whether it is caste, religion, or familial bonds, the tyranny of the “acceptable” continues to strangle the personal.

Society finds comfort in binaries—what is permitted and what is forbidden, what is sacred and what is profane. But Narayaneente Moonnaanmakkal dissects these boundaries, exposing the hollowness of moral absolutism. What is love if not a force that transcends the rules set by those who came before? The true discomfort is not in Aathira and Nikhil’s love, but in a world that insists it should not exist. The film does not offer easy resolutions; instead, it lingers in the space between rebellion and restraint, inviting us to question not just the characters’ choices, but our own deeply conditioned responses.

More than anything, Aathira and Nikhil do not exhibit even the faintest desire for marriage or an ordinary life. They assess their parents—not with love, but with a sharp gaze filled with resentment and disregard. The question lingers: Are parents merely the people we see on the surface? How long can they continue their performance before their children? The veils of dignity they wear eventually slip, revealing a truth too raw to ignore. In such a climate of disillusionment, where belief itself is fractured, why would they willingly leap into the same cycle of marriage and parenthood?

Moreover, when Vishwanathan uncovers their relationship, Nikhil’s first instinct is to flee. He is not staging a grand rebellion; rather, he is caught in the web of traditional moral authority, unable to fight back, forced to endure. They do not nourish any naive hope that their love will triumph over the rigid structures that surround them. There is no illusion of a future where they can simply outlive these societal constraints and emerge victorious.

At the same time, they are not the kind of people who would wallow in shame, crushed by the weight of guilt, like the protagonists of a “Drishyam-style” moral drama. They do not believe they have sinned. They live by their own rules, unburdened by the expectations of those who themselves are lost in the grand performance of life. Why should they look up to them, emulate them, or obey them? Aathira makes this clear when she bluntly responds to her mother (Sajitha Madathil), who scolds her for not applying for a PSC job.

Sharan Venugopal’s film does not merely use the dialects and landscapes of Koyilandy to anchor its narrative—it plunges into the shifting realities of Northern Kerala. The transformations of an entire century are reflected in its frames. In Sethu’s grocery store, when a caste-conscious customer comes searching for a ‘Brahmins curry powder’, Sethu dismisses his concerns: “There’s only one kind of curry powder here—for everyone.” He hands him an unbranded packet, obliterating the hierarchies of purity with a simple act. Above this very shop, the local committee office of the Communist Party of India (Marxist) operates. The red board that hangs there is not just an aesthetic choice—it is a reminder of the political forces that have shaped Kerala. The film does not diminish, obscure, or mock this reality; rather, it embraces it.

As critic Rupesh Kumar notes, Narayaneente Moonnamakkal meticulously documents the intricate entanglements of caste, community, and economic shifts. His reflections, shared in a Facebook post, are significant:

“For me, Narayaneente Moonnamakkal is a powerful text that portrays, from the ground up, the complex historical trajectory of the Thiyya community in Koyilandy and Northern Malabar. Even the regional dialect in the film roots it firmly within a specific geographical identity.”

This film constructs a strikingly different visual language—through the architecture of a grand Thiyya household, through the portrait of Narayana Guru adorning its walls, through the vast courtyard that lies at its heart. This is not just an aesthetic choice; it is a representation of a community’s evolving position within Kerala’s rigid social stratification. The characters do not exist in isolation—they are shaped by the paradoxes of progress and stagnation, by their moments of ascendance and their sudden falls.

Vishwanathan’s interactions with his younger brother are not just familial conversations—they are infused with the weight of history. When he speaks of love and interfaith marriage with a condescending thanta vibe, the scene becomes a reflection of the long-standing tensions between Kerala’s savarna past and the communities that have constantly resisted and negotiated their place within it. The film does not push an overtly political morality onto its characters, nor does it reduce them to ideological mouthpieces. Instead, their lives unfold organically, revealing the psychic and social transformations that have shaped their world. Sometimes, the film even permits moments of political reaction, though it does so without forcing a rigid narrative.

It also acknowledges how Hindutva ideologies have started permeating the internal fabric of these communities—evident in the subtle yet significant exclusion of a Muslim woman from the chettan/ulsava parampu space. Sethu’s (Joju George) composed defiance that dismisses the orthodoxy with quiet confidence adds depth and strength to the character.

This stratification is not just theoretical—it manifests in generational divides. Suraj’s character, Bhaskaran, leaves for the UK, marries a Muslim woman, and yet his own son cannot tolerate him. Meanwhile, Vishwanathan, who remains bound to his old ways, is viewed with pity by his own daughter. Here, the film forces us to reconsider old definitions of exposure, education, travel, and progress. It is the children who bring forth new conversations, who expose the dark secrets buried within the family, even in moments of humor. When Sethu dismisses caste by saying, “There’s only one kind of sambhar powder here,” it is both a joke and a quiet act of defiance. The same Sethu, with his seemingly inconsequential habits—smoking weed without pretense, nurturing an ambiguous love in the ulsava parampu—becomes one of the most nuanced and intriguing figures in the film. Joju George plays this role with effortless brilliance, embodying a character who does not seem to belong in this Kerala at all.

The character of Vishwanathan echoes a historical shift that reminds one of Kathapurushan, where Mukesh played a wealthy backward caste man attempting to buy the ancestral home of an upper-caste Namboothiri family. In Narayaneente Moonnamakkal, the reversal is equally striking: here, a savarna character returns to reclaim lost land, only to be met with resistance. “They inherited it, but we built it with our own labor,” Vishwanathan says, justifying his stance. This dialogue feels like a delayed response to an unsaid moment in Kathapurushan, a reflection that Kerala’s visual politics have evolved through decades.

At its core, Narayaneente Moonnamakkal is not just about the Thiyya community—it is about the generations of struggle, transformation, and confrontation that define Kerala’s history. The film does not simply depict this journey; it lives within it, breathing the air of a land shaped by centuries of conflict and change.

This article was originally published in Malayalam in The AIDEM. Translated to English by Sania KJ.

A truly exceptional review of an exceptional film , thank you GP Ramachandran

Outstanding review, which makes me want to revisit the movie with newer insights. I was wondering why the movie did not make enough waves in the halls. After seeing it on OTT, I realise that the movie requires deep engagement, probably untrammelled by the overpowering audio systems unsuited to sensitive portrayals in the halls. Superlative performances by Joju, Gargi and Thomas. Thank you for the review.