S Jayachandran Nair, the Editor is no more. He passed away in Bangalore yesterday, at the age of 84. I saw social media flooding with obituaries. Lately, I have been writing too many obituaries. In some ways, obits are also the best genre of writing because they are written in absolute reverence of and love for the person who has just gone out from our lives.

However, I kept postponing this article. I was afraid Jayachandran sir might strike off a few lines from this obit, going through it with the critical eye of the serious editor that he was. I was apprehensive that he would think that many parts of this piece have gone over the top and are replete with unnecessary superlatives and eulogium. He was a rebel throughout his career and till his last day, I would say.

Saji James, the current editor of Samakalika Malayalam Vaarika, founded by Jayachandran Sir, called to inform me that our dear mentor was no more. I was shocked despite my firm conviction that death was the only guarantee of/in life. Then, I felt a sense of pride that Saji had found it fit to add me too to the list of people who have to be personally informed of the grand man’s passing. The writer that I am today is essentially a chisel work of Jayachandran Sir (JS).

JS was the editor who established many a journalist’s career. He was a cub journalist in Malayalanadu weekly, where the renowned literary journalist, Prof. M. Krishnan Nair had started his pathbreaking column, Sahityavarafalam, loosely translated as Weekly Horoscope of Literature. It was a sort of avuncular take or guide that sought to help Malayali writers find their direction out of the wilderness of mediocre writing. In the mid 1980s, JS moved to Kalakaumudi, another weekly that the Malayali Buddhijeevi (intellectual) thought was an essential item in their reading list. He brought M. Krishnan Nair and artist Namboothiri, who after Raja Ravi Varma, remoulded the visual sensibility of Malayalis through his illustrations, to Kalakaumudi, making it a worthy rival to Mathrubhumi, which could till then claim the position of the sole arbitrator of Malayali’s literary tastes.

JS created a new benchmark for Malayali’s literary taste (of course, he had respected certain continuities as well) and rewrote the rules of publication of weeklies in a fast-growing literary market of the 1980s. One could say that today’s flourishing publication industry in Kerala is just a byproduct of the kind of journalism, an approach mixed with facts, taste and flair, established by Jayachandran Sir.

Truecopy Think, the online magazine established by Kamal Ram Sajeev, the former editor of Mathrubhumi Weekly and also the style changer of Madhyamam (another prominent weekly that invests on a lot of subaltern issues; socio-political and aesthetical), has a qualifying subtitle, ‘readers as thinkers.’ This online venture has made many social media writers into writers with an invisible editorial direction. I would say that Truecopy Think and many other online journals including the CUE and The AIDEM, in a way continue the ‘JS style’ of journalism.

Moving from a cash rich Malayalanadu was not an easy task for JS. Kalakaumudi had a reputation and acceptance but did not have the coffers to pay off all the writers. JS found out a way. He handpicked a few writers who were showing up in small time publications even while sending in their work for his consideration. They were either college students or youngsters with journalistic acumen. He established their bylines. P K Rajasekharan, Viju V Nair, Sajeevan, Vinayakumar, Anvar Ali, Unni Balakrishnan, Venu Balakrishnan, P M Binukumar and many others became household names in Kerala.

I believe that it was JS who made many young graduates take up post-graduation in journalism or diploma in journalism. Those were the pre-TV channel days and Kalakaumudi was a prestigious platform for the youngsters. Interestingly, while the seniors stood with JS when he walked out of Kalakaumudi in 1997, the youngsters had found their positions in the mushrooming Malayalam TV channels.

As a student in Thiruvananthapuram, I wished to write in Kalakaumudi but never had the courage to approach JS or send articles to him. I was living a stone’s throw away from the office of Kalakaumudi in Pettah. I remember reading Mein Kampf sitting on a park bench next to the Kalakaumudi office. But I never dared to walk into the office. Maybe, in those days I was distracted by many other things.

However, I read Kalakaumudi diligently and noticed the style of journalism flowering in its pages. Kerala magazines were famous for its sentimental features and reports. If you wanted to read serious journals you had to go for Bhashaposhini from the Manorama stable or Mathrubhumi, from the GOP (Grand Old Press). JS was the first one to find a fine balance between sentimental features and semi-academic journalism. Viju V Nair excelled in that style. Youngsters wanted to emulate his style. JS whole heartedly encouraged such writing.

Life is a game of chances. JS leaving Kalakaumudi shook up the world of journalism in Kerala. Its repercussions were felt even in Delhi. Everyone curiously waited for his next move. In August 1997, JS launched Samakalika Malayalam Vaarika, funded by Manoj Sonthalia of the New Indian Express Group. The whole team moved with him to the NIE office in Kaloor, Kochi.

My tryst with JS and Malayalam Vaarika happened in the same month. Cartoonist Unny (EP Unny of the Indian Express) sent a message to me through a common friend. JS wants to talk to you’. I couldn’t believe my years. Those were the pre-mobile (phone) days. I was supposed to take the call at Unniyettan’s office. My name was already in the Delhi journalistic circles as an art columnist and cultural reporter. That must have been the trigger. I believe Unniyettan must have suggested my name to JS as the Delhi Correspondent.

I heard Jayachandran sir’s voice for the first time. He called me ‘Jaani’, the old way of pronouncing ‘O’ as ‘A’. I immediately agreed to take up the job. I had no training in journalism. But I knew how to handle language. I thought Unniyettan would help me in shaping up my ideas. To tell the truth, I couldn’t even differentiate between Kalyan Singh and Mulayam Singh in those days. But I had a sense of politics and I was following the political changes of India since 1984, a year marked by the assassination of Indira Gandhi, passing of my father and the Bhopal Gas tragedy.

People who read Malayalam Vaarika from 1997 to 2002 knew my name well. I was reporting Delhi affairs almost comprehensively. My features were acclaimed and I used to get fan mails. I remember in 1999, during a state government festival in Kerala, after my speech, college students coming to take autographs from me. They used to read my articles regularly in Malayalam Vaarika.

Interestingly, I worked under Jayachandran Sir’s editorial guidance for over three years without meeting him even once! Those were pre-skype, pre-whatsapp, pre-google meet, pre-video call days. I had a land phone. Once a week JS would call me and give me leads to follow. He asked me to meet Narendran sir of Kerala Kaumudi. Narendran Sir was a veteran journalist. Sitting stately before his Remington Typewriter and smoking non-stop, Narendran sir told me stories about his days of active journalism. It was a sort of Zen learning. He did not teach anything particular but there was something to take home in every story.

A couple of years ago, I got into an argument with an FB friend who said whoever had the Savarna surname (Nair particularly) stood for Brahminical values. I told the friend that the older generation used the surname as a part of the name, not as a title. Definitely, the surname had given them a leverage and social capital in a caste ridden society. But calling one and all as Brahminic was wrong. The case of JS was different.

A young rebellious Jayachandran was just ‘S Jayachandran’ when he was in Malayalanadu. As he moved to Kalakaumudi, an Ezhava establishment, the management wanted to tell the world that they were not caste-biased, and they could entertain a Nair in their establishment. It was MS Mani, the MD of Kalakaumudi who changed S Jayachandran into S Jayachandran Nair… But the case of Narendran Sir was slightly different; he started off as Narendran Nair. But when he was sent to Delhi by Kerala Kaumudi group to represent the daily in Delhi, they wanted to tell the world that an Ezhava establishment has an Ezhava representative in Delhi. So, the Nair part was removed and Narendran Nair became ‘Narendran’.

In 2000, for the first time I met JS at his office in Kaloor, Kochi. I knocked at the door and entered the room. At the far end, he was sitting behind a large table and reading some manuscripts. He raised his head and looked at me and asked nothing. Embarrassed, I said, ‘Sir, I am Johny ML .’ ‘So, do you expect me to stand up and salute you?’ was the answer. For a moment, I was dead. Then he burst out into laughter. I joined the mirth. We had tea together. My wife, Mrinal, was with me. He took us to his home and dropped us off at our hotel after dinner. The relationship remained cordial till I decided to stop writing for Malayalam weekly regularly after 2004 . The cordial relationship continued even after that. I never severed my relationship with Malayalam Vaarika. Till 2018, once in a while I used to write an article or two under Saji James as the editor.

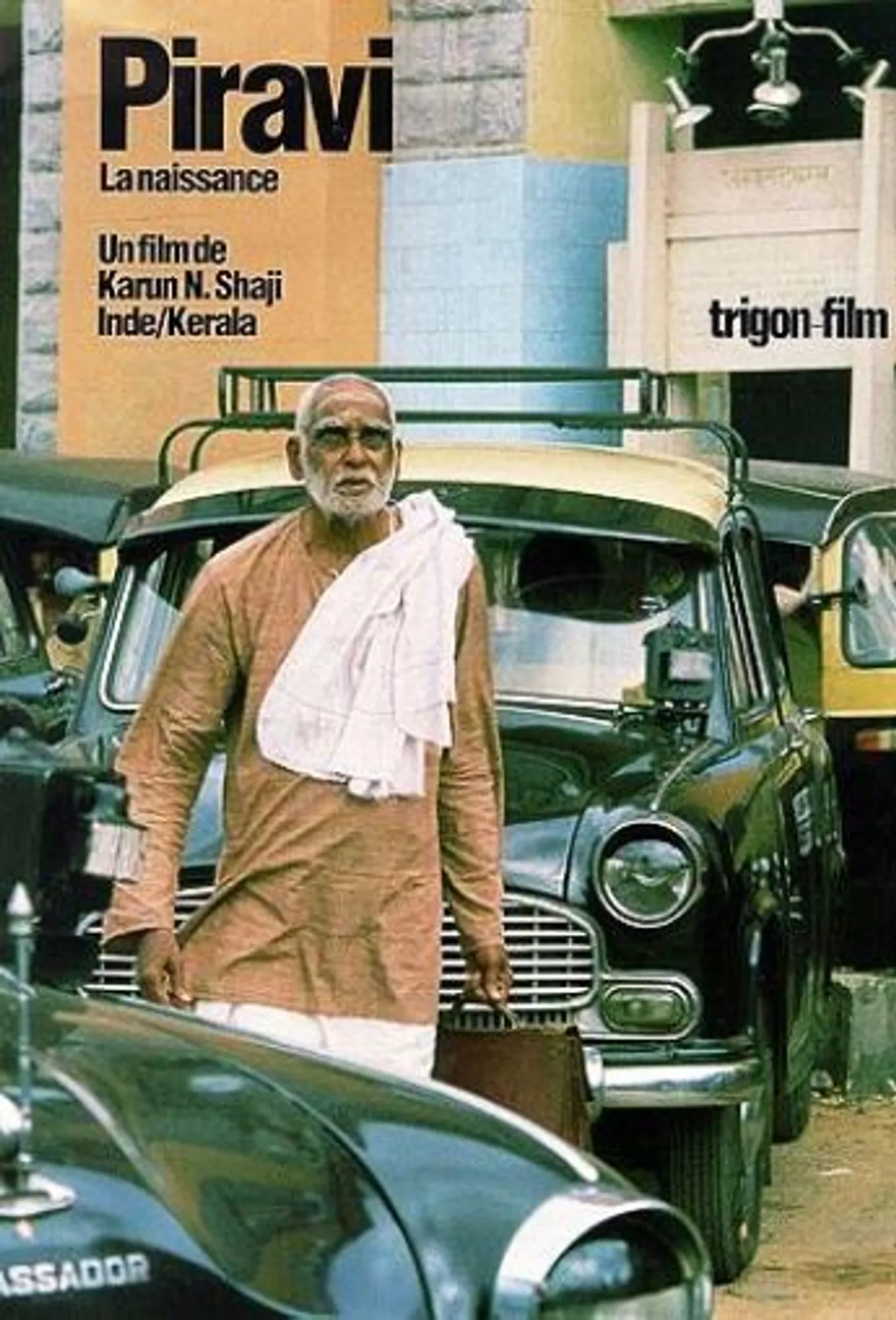

JS was an avid reader and writer, but shunned the limelight completely. He wrote scripts and produced films; Piravi and Swam by Shaji N Karun happened because JS believed in those movies. I always felt that JS had strangely identified himself with Premji’s character in Piravi; father of a murdered young man, fighting for justice and waiting for his return in vain. JS did not have similar experiences in his own life but he certainly identified with the stubbornness of the father in the movie ; the stubbornness of a father seeking justice for his dead son , who was killed by the machinations of State machinery.

JS journalism career had manifestations of this streak, starting with his expose of forest robbers (the timber mafia) of Kerala in the 1970s. He stood for his generation of talented people and his faith in their contribution was unchallenged. Once, in one of my articles about KCS Panicker, the artist, I wrote a line that was a bit critical. He used his blue pencil on that line and told me, ‘Jaani, you need to grow a few more years to write that line.’

Writing came quite naturally to Jayachandran sir. He wrote a novel and it was about a man contemplating suicide. It was quite unexpected from a senior journalist of his stature who looked absolutely sorted and beyond any confusion about his mission in life. He titled his collection of essays, ‘Rosadalangalum Kuppichillukalum’ (Rose Petals and Glass Shards). He always looked simultaneously at the fairer and harsher sides of life, art and literature. Finally, he wrote his autobiography, ‘Ente Pradakshina Vazhikal’ (Paths of My Circumambulations), which definitely shows his faith in the geniuses who showed way for him, and his devotion to them.

I met JS for the last time in 2018 at Thycadu Guest House in Thiruvananthapuram where I was staying for a week to finish a manuscript meant to be published by Kerala Lalitha Kala Academy. I met him quite unexpectedly in the dining hall, as he and his wife were eating their extremely frugal breakfast.

The first thing I noticed was the un-pressed white shirt and its carelessly rolled up sleeves. Two buttons from the top were open; something one cannot expect from that giant of a man who always preferred to wear starched and ironed white Khadi shirt and dhoti. I could see his weak chest, once so formidable that it withstood mafia and political thugs. I averted my eyes. I remembered the lines of N N Kakkad, the poet, “Let me stand near this window… You be there next to me, with a cough this old cage may fall shattered’. JS talked to me, asked about my projects, my writing and my life. I sat with him for a while and went to pick up my plate. I saw them walking towards the door, almost supporting each other.

But Jayachandran sir lives on through those youngsters – many of them are now in their fifties and sixties – whom he had handpicked and remoulded as journalists, writers and observers of life and the world.

Thanks Johny for your insights into JS The Editor of our times. Sadly for all of us who knew him , the void will have to be accepted. Perhaps with time we may reconcile to this harsh reality. Nevertheless life must go on…